The Perspective Research Centre (PRC) is a research and educational centre focused on perspective and the visual dimensions of art, science, and technology.

We begin by asking: What is perspective? A simple answer is that perspective deals with natural perspective, including visual perspective, or how we see things, and artificial perspective, or how we represent that concept in diagrams, drawings, pictures, photographs, films, television, computers, etc.

Given such a straightforward definition, one might assume there is little to learn and label perspective as a standard visual method involving well-known principles. However, nothing could be further from the truth. It turns out that many different kinds of perspectives exist with complex characteristics, often presented with unexplained ‘facts’ that work to confuse, along with perplexing mysteries and exciting possibilities. Our task is to help you learn about and explore the kaleidoscopic, sometimes highly technical and wide-ranging topic of perspective and to unlock new abilities/solutions along the way.

Herein, you will find a vast archive of information on perspective, including a subject Library, Encyclopedia, Bibliography, and Dictionary, plus links to countless publications on this seminal topic. We have spent over three decades gathering, indexing, and organising this unique knowledge bank to provide easy access to everything known on perspective.

We hope you find these resources informative, helpful, and enjoyable.

Status of Perspective

Perspective is our chief method of visualising the world, obtaining a systematic treatment of <depth::size> and <aspect::shape>, plus establishing a visual standard of truth. It works in two directions: to record an image backwards onto a picture plane, and to project an image/light-beam/shadow forward into physical reality—leading to a scientific understanding of three-dimensional structure(s).

A familiar form of optical/graphical perspective is linear, Renaissance or scientific perspective, which we learned at school: It asks how to draw a picture on a plane surface that represents a three-dimensional object/scene in such a way that the various portions of the picture, in their mutual relations, present the same aspect as do the corresponding visible parts (or outlines) of the object/scene. Ergo, linear perspective rationalises vision by prescribing, segmenting, ordering, indexing, and gauging physical space.

In truth, we have countless ways to view/depict/measure spatial reality. Accordingly, there are different classes of perspective, including visual perspective for observing, instrument perspective for surveying/recording/displaying, simulated and new media perspective for constructing/modelling spatial objects/scenes, etc. Perspective is a multi-faceted subject that covers a far wider range of visual phenomena than many realise; it is also a key to understanding major categories of art/science/technology. Related topics include space, time, optics, human eye/vision, colour, drawing and geometry, painting, reality, illusion, imagination, and representation.

Perspective is central to key developments in various subjects, including photography, television, cinema, cartography/maps, astronomy, topology, photogrammetry, scenography, archaeology, architecture, gardens and environment, etc. Recent developments also have strong links to perspective, such as Geographical Information Systems (GIS), Global Positioning Systems (GPS), Virtual Reality (VR), Computer Graphics (CG), Computer-Generated Imagery (CGI), Computer Vision (CV), Artificial Intelligence (AI), digital filmmaking / virtual production, medical imaging, robotics, stereography, panoramas, holograms, and space flight.

In sum, perspective lies at the epicentre of progress and is pivotal to everything humans will achieve in the future. QED.

Our Mission

We seek a unification of perspective knowledge across all subject disciplines.

A basic goal is to gather perspective theory/methods as developed in both Western and non-Western cultures; and to foster rational insight into the various classes/categories/forms, technical systems, practical applications of perspective, and associated visual media. By collecting, linking, and developing perspective knowledge, we can support education and technology development across a range of artistic, scientific, and cultural disciplines.

All types of perspective are studied, falling under natural, artificial, and synthetic classes; leading to detailed analysis of visual, graphical, mathematical/geometrical, linear, curvilinear, cylindrical, spherical, aspective, negative (reverse/inverse/inverted/diverging), proto/pseudo, axial, birds-eye, parallel, modular, glide, accelerated, anamorphic perspectives, etc., plus various kinds of simulated, illusive, augmented, or virtual perspectives and mixed real/digital forms.

But why study perspective today? Surely, it is a well-understood, essentially historical topic, mainly of interest to artists, designers, and architects. Indeed, perspective has been and continues to be, eminently useful as a graphical technique for depicting/modelling/enhancing spatial realism. However, perspective is also a scientific discipline closely linked with modern innovations, including Computer-Aided Design (CAD), Medical Imaging (MI), Computer-photography, 2-D/3-D cinema, Special Effects (SFX), Virtual/Augmented/ Mixed Reality (VR/AR/MR), computer games, digital filmmaking, etc.

Perspective drives artistic, scientific, and technical progress to a great degree. Nonetheless, perspective likely has countless other applications—types/methods/facets—that have yet to be discovered. Unfortunately, even the known perspective forms are mired in complexity today, and a complete cataloguing of all classes/branches has not been performed.

We aim to combine all perspective knowledge into a single framework: perspective category theory (PCT), heralding the birth of perspective science as a primary branch of knowledge—with established theory and, above all, unified laws.

Origins

The Perspective Research Centre (PRC) has a rich 30-year history.

PRC developed from two past organisations, the Perspective Unit at the University of Toronto and the Maastricht McLuhan Institute (MMI). We have inherited an important scientific legacy from these organisations, including the Library, Bibliography, Encyclopedia of Perspective, etc.

For over 30 years, Kim Veltman (1948-2020) was the world’s number-one expert on perspective and founder and director of these organisations. Following his sad passing in April 2020, PRC maintains the official papers of Professor Kim Veltman’s lifetime works—as collected in the Kim Veltman Archive, including unpublished articles, letters, books, treatises, and other manuscripts. This incredible knowledge bank consists of 2.9 million words and 10,000 pages spread across over 400 publications on perspective and related topics, making Kim one of the most prolific scientists ever.

Today, our work continues as we progress towards a single access route to all knowledge on perspective.

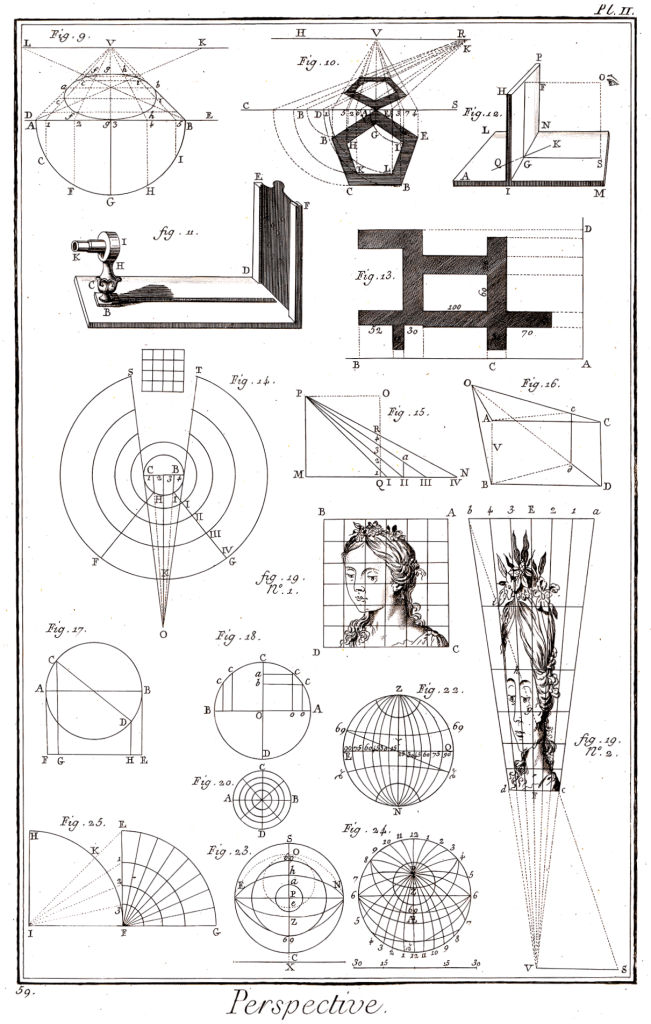

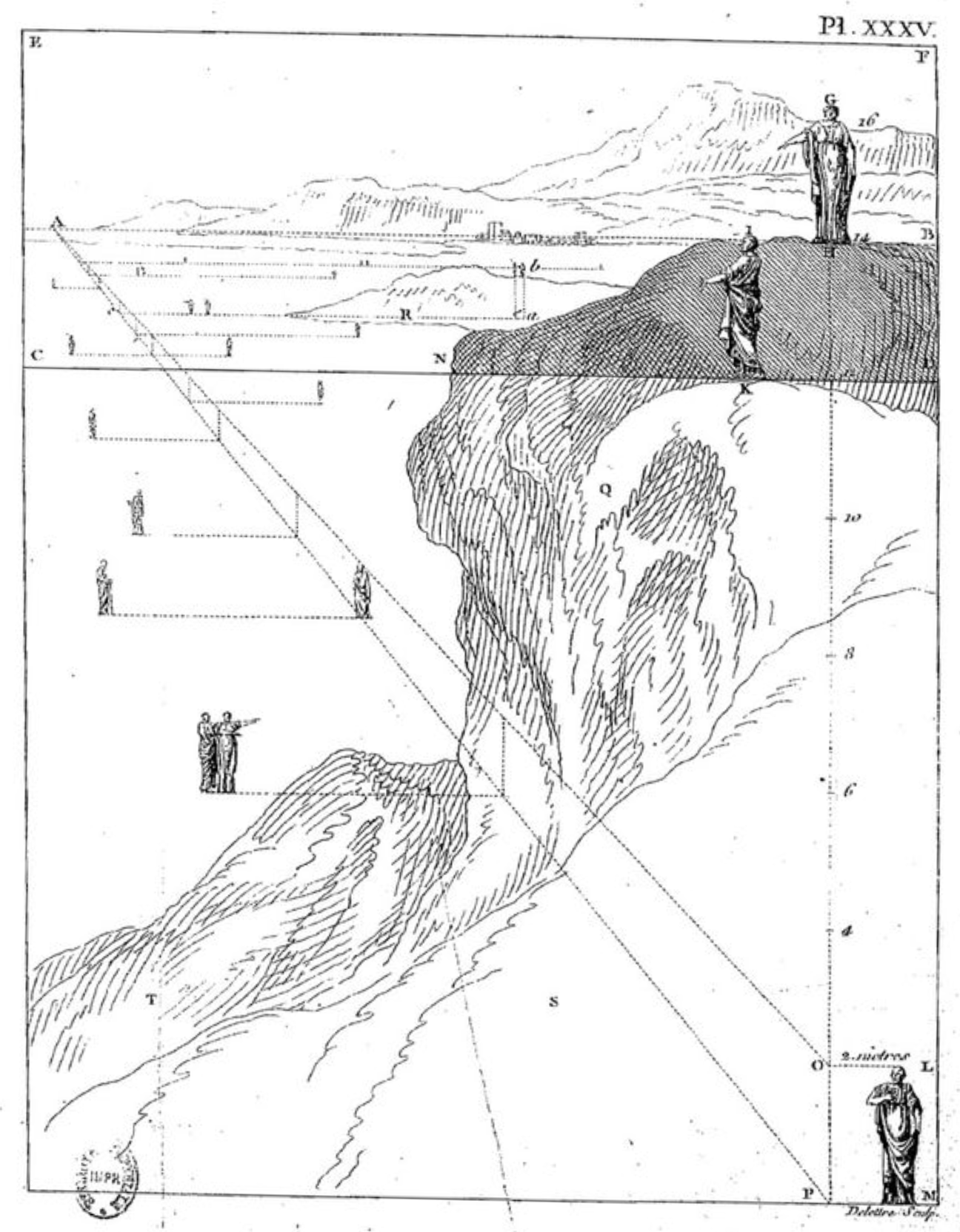

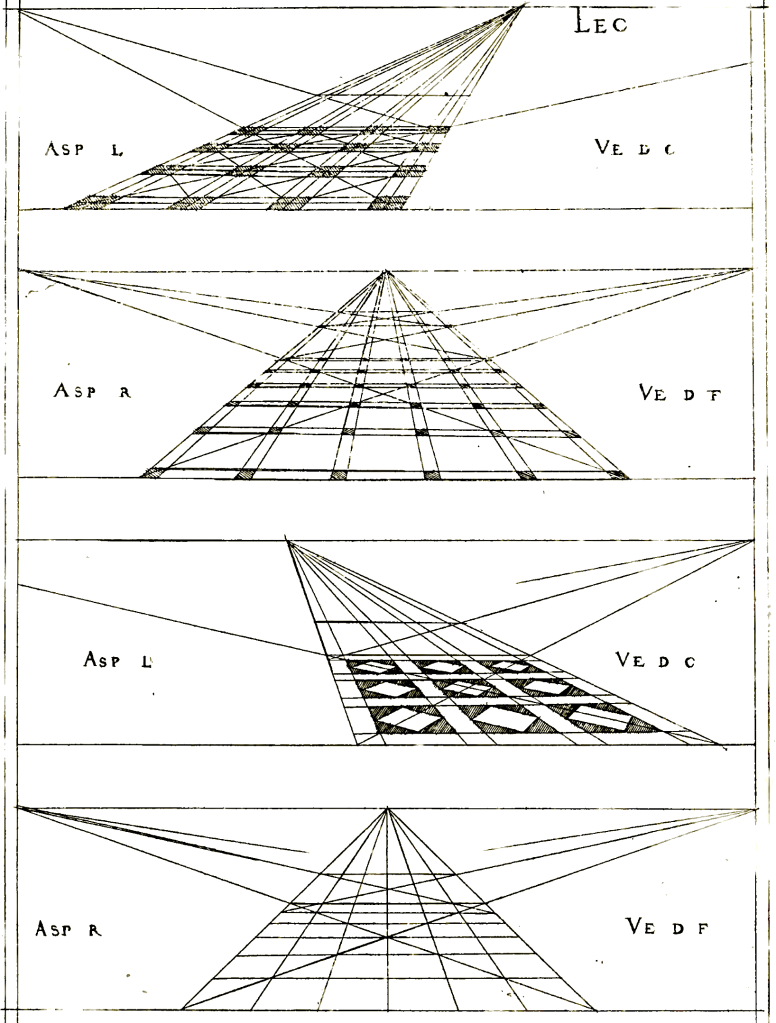

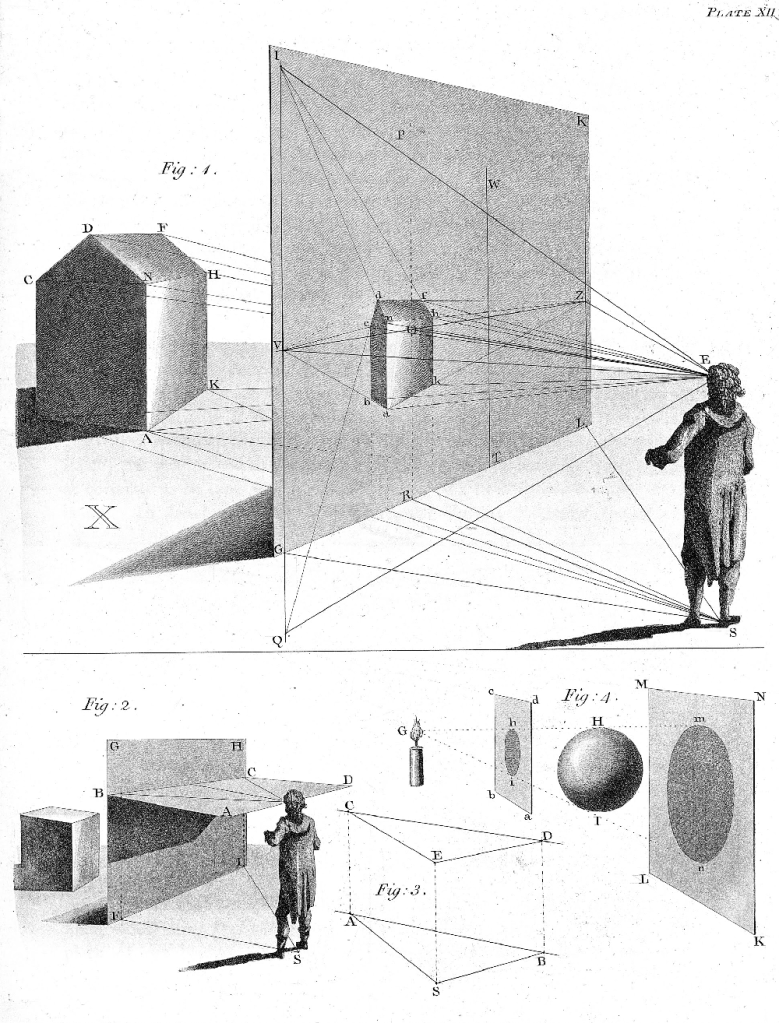

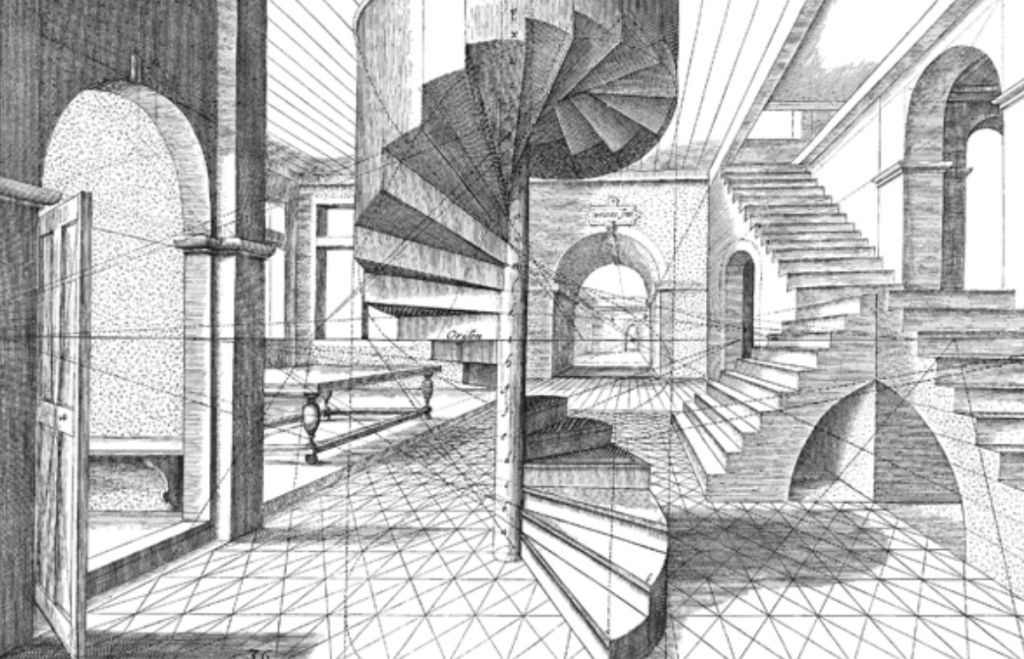

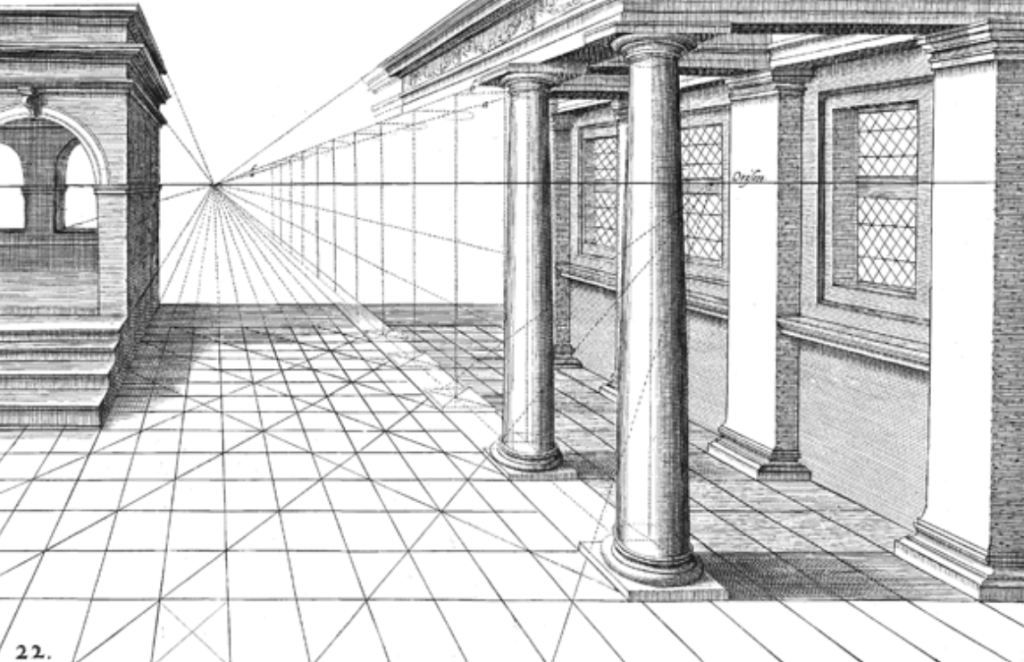

Figure 1: Linear / visual / anamorphic perspective drawings (16th – 19th c.)

PRC curates several scientific archives on perspective, including the complete works of past collaborators: Professor Marshall McLuhan (1911-1980), Professor Sir Ernst Gombrich (1909-2001), Professor Luigi Vagnetti (1915-1980), Professor B.A.R. Carter (1909-2006) who was professor of perspective at the Royal Academy, Professor Kenneth Keele (1909-1987) who was president of the Royal Society of Medicine, and Professor A. I. Sabra (1924-2013) a world-leading expert on the history of optics and science in medieval Islam. Founder Kim Veltman also worked closely with human vision experts Professor(s) C.B. Schmitt (1933-1986), A.C. Crombie (1915-1996) plus R.A. Weale (1922-), and we hold detailed records of these collaborations.

Doubtless, this is sufficient introductory information on our own history (of the Perspective Research Centre), as the visitor/reader is likely more interested in the history of our primary subject matter.

The Epic Story of Perspective

Renaissance, linear, or so-called one-point perspective is a geometrical construction method thought to have been devised about 1415 by Italian Renaissance architect Filippo Brunelleschi and later documented in Della Pittura by architect Leon Battista Alberti in 1435. The discovery of this form of linear perspective was an epochal moment in the Western artistic and scientific tradition(s).

A little over 2,000 years ago, the ancient Greeks developed the first systematic attempts at a realistic depiction of depth on a flat 2D surface, employing key perspective phenomena. These phenomena include apparent diminution of size with distance (size/distance formula), apparent diminution of form (loss of outline detail with distance), apparent degradation of form (object shape distortions with viewing angle), aspect foreshortening (viewing direction apparent contraction of size), plus vanishing points, among others. However, it is believed that they failed to develop/understand/apply the basic principles/methods of linear perspective; whereby, it is assumed that all objects must be viewed from a single point of view, and further that each set of orthogonal (parallel) lines must converge to a single primary vanishing point.

The roots of linear perspective arose in the Near East, including Egypt and West Asian countries from the Arabian Peninsula, northeast Africa, as well as in the Arabian and Ottoman empires, with countries like Iraq, Yemen, and Jordan. Ergo, we are dealing with the Egyptian, Byzantine empires, etc. Regarding the role of true Far Eastern countries like India, China, and Japan, much less is known or established in terms of the history of graphical/linear perspective.

Ancient Egyptian hieroglyph depictions from approximately 3100 years ago are based on ‘flattened’ image montages, which do not account for the effects of recession, diminution of size, or degradation of form. Some rare ancient Egyptian/Mexican paintings do show foreshortening, but these examples, being so few, must be attributed to either accident, unconscious practice, or individual artistic technique.

In contrast to Egyptian, Byzantine, and Indian Art, early Chinese and Japanese Art did employ the perspective element named as recession of apparent size (non-systematically), but once again without the use of vanishing points or (object) aspect foreshortening as seen in the Ancient Greek examples. Japanese images of expansive scenes employ oblique parallel projection. In addition, Japanese images make heavy use of aerial perspective to represent distance, in terms of colour, atmospheric, and contrast perspective(s). In particular, Japanese Art often took the form of scrolls, which unrolled time/space to tell a story, producing a type of conjoined never-ending space. The single viewpoint and central vanishing point of linear perspective are missing; hence, the space is not unified and is, in any case, not intended to depict a single viewpoint taken at a snapshot in time.

Whilst perspective has foundations deeply rooted in the past, it remains a distinctly modern subject. Nevertheless, older principles, theories and perspective methods remain highly relevant to the contemporary world and its myriad of visual technologies. Indeed, the budding perspectivist has much to gain from a close study of the history of perspective.

Perspective Today

Perspective is by no means an old, abandoned, or dead subject. On the contrary, today, we see more types and applications of perspective than ever before.

Perspective instruments, such as telescopes, microscopes, cameras, and images on television, computer and mobile screens, take perspective methods to a new level of usefulness. And the diverse techniques of mathematical perspective have been applied to a vast range of problem areas in many fields of endeavour outside of the mere aesthetic representation or imaging of spatial objects and scenes. For example, perspective techniques lie behind spatial problems in astronomy, space flight, surveying, geographic information systems (GIS), cartography, navigation, photogrammetry, weather monitoring systems, medical imaging (MI), computer-aided design (CAD), commuter vision, special effects (SFX),Virtual / Augmented Reality (VR/AR), Global Positioning System (GPS), computer-chip manufacturing, etc.

Today, the primary methods/systems of perspective are significantly improved in power, scope, accuracy, and the sheer number of eminently practical application areas. Perspective is the preeminent way for humans to image, view, match, represent, and create illusions of, or immersions into, a universe of visual complexity. And by utilising advanced perspective methods/systems/instruments, we vastly expand the field/range/depth of human vision.

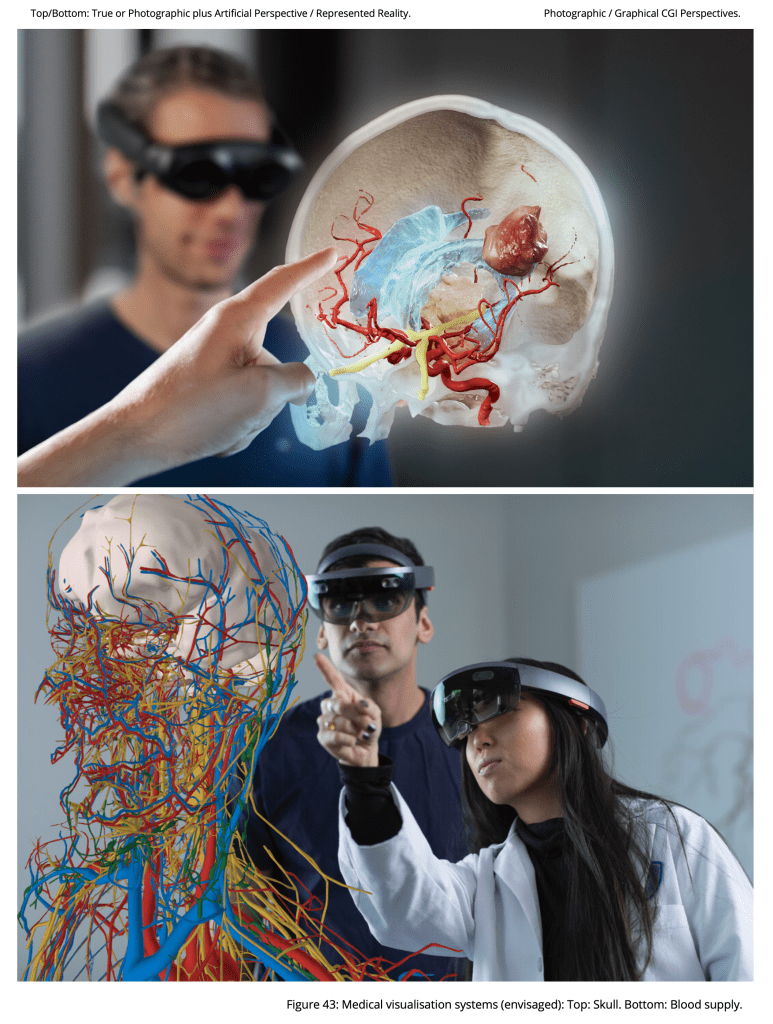

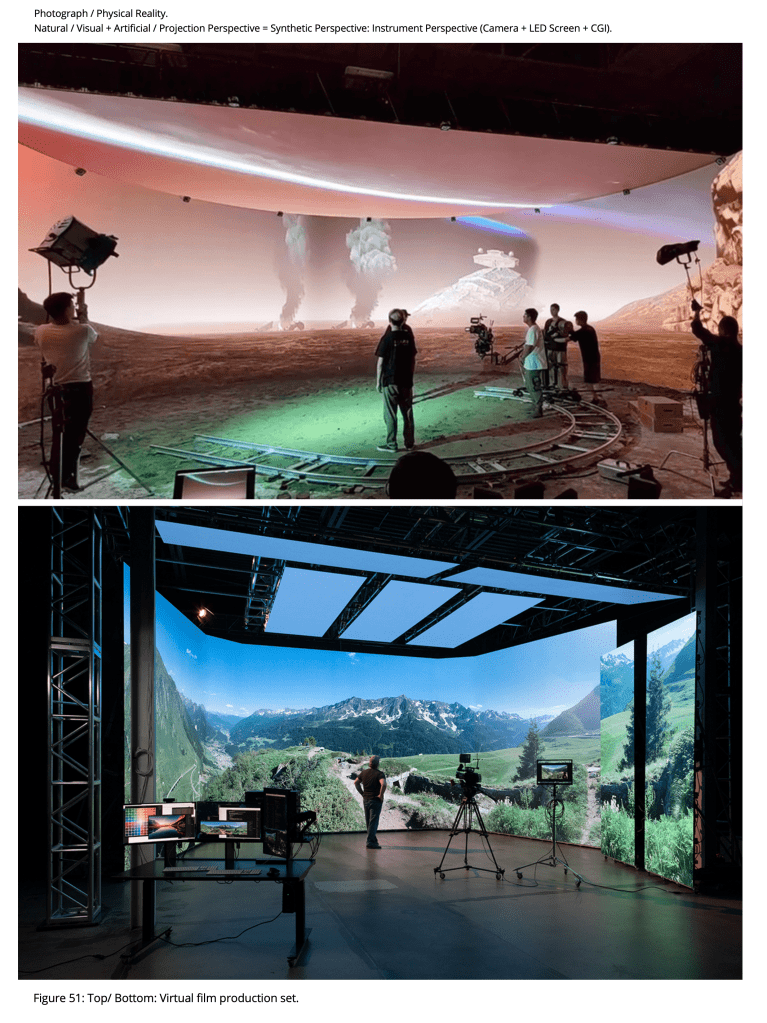

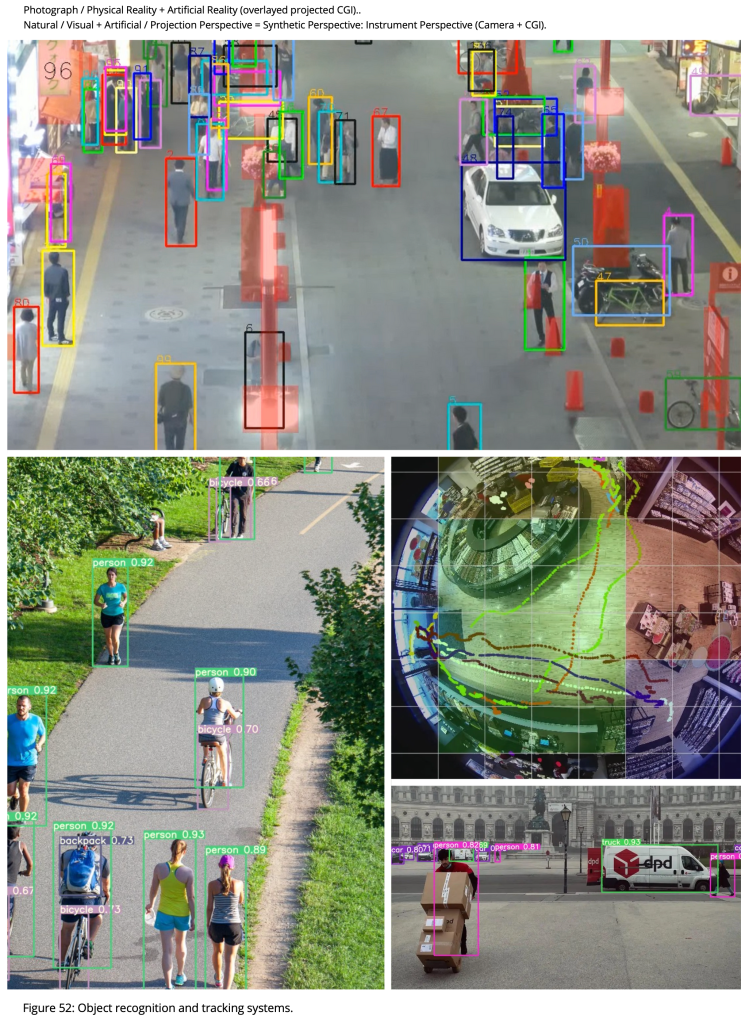

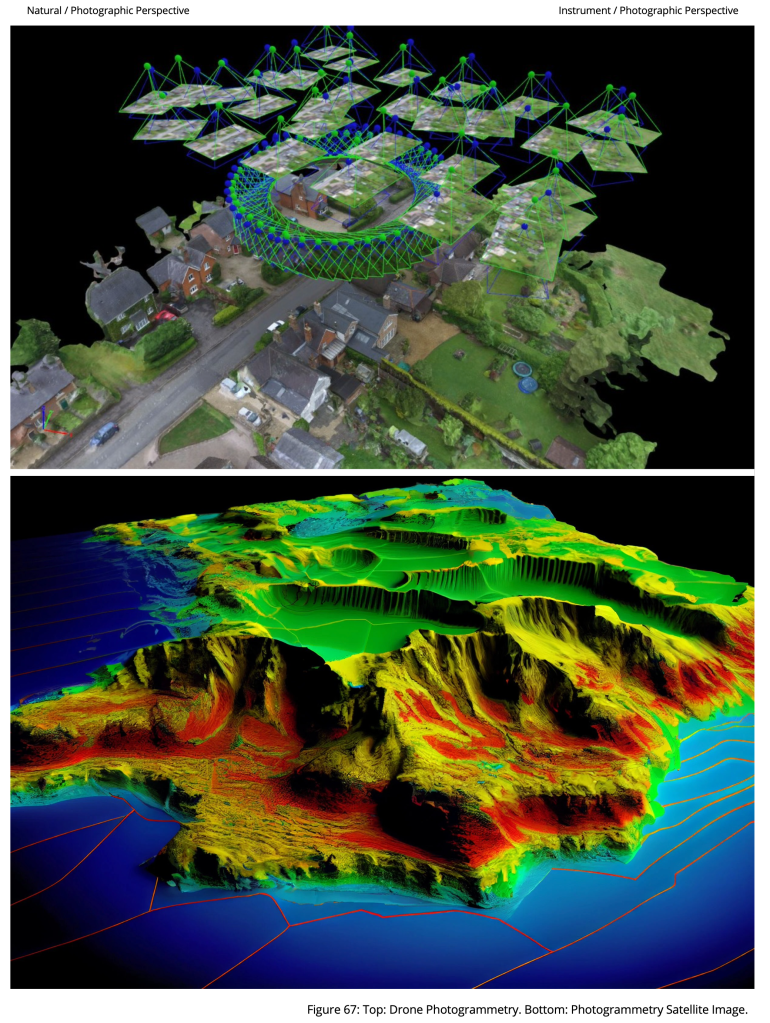

And given the unprecedented triumphs achieved by the history of perspective, who can say what incredible heights perspective can take humanity to? Indeed, today, new perspective techniques are being applied to visual problems in specific fields, such as drone displays and photogrammetry, robotics, medical visualisation, virtual film production, object recognition and tracking systems, automated vehicle driving systems, and new astronomical/microscopic systems, as well as being observed as overt perspective phenomena in Artificial Intelligence images and videos.

Figure 2: Modern perspective methods/systems (clck to expand)

The various types, principles, phenomena, methods, systems, and instruments of visual/optical/technical perspective underlie all such innovations. Ergo, today’s perspective images are more detailed, colourful, distinct, wide-field, and realistic. Plus, perspective views/images—of both still and moving kinds—are far more numerous, relevant, and readily available, and thus impactful, than ever before.

We can conclude that the various perspective principles, types, methods, systems, and applications have been, and continue to be, indispensable to the development of human civilisation as it exists today.

Library, Bibliography, and Encyclopedia

The PRC curates an extensive collection of unique and world-leading materials on perspective and related subjects.

Established over 50 years, our Library of Perspective consists of 5,000 physical volumes (catalogued), 10,000 digital papers/books (uncatalogued), hundreds of articles/theses/treatises, and 33,000 digital images. A meticulously assembled Library Catalogue [60 MB pdf] has been produced, detailing the Library of Perspective, whereby modern scholars can browse the contents and seek out interesting works for themselves.

Today, the Library of Perspective is unsurpassed in the private field, and in the future, we shall continue collecting new materials on perspective. The library aims to collect all specialised literature in the field(s) of perspective, projection methods, spatial concepts, imaging and vision.

PRC maintains the standard world Bibliography of Perspective, initially developed by Professor Luigi Vagnetti and later progressed by Professor Kim Veltman—who together spent 90 years compiling a list of 15,000 perspective titles from throughout time. You can access the bibliography here: Bibliography of Perspective: Volume 6: Antiquity-1899 [4 MB pdf], Bibliography of Perspective: Volume 7: 1900-2020 [6 MB pdf]. In 2020, PRC published the bibliography as part of the Encyclopedia of Perspective (2,500 pages), the definitive work on its subject matter that is a wonder to behold.

Leonardo da Vinci

Italian polymath Leonardo da Vinci was an early pioneer of perspective techniques, employing a supremely visual approach to his remarkably inventive studies of the natural/built world(s).

Leonardo developed a comprehensive theory of perspective that contains definitions, principles, and explanations that are remarkably modern in form. Leonardo probably knew more about optics, vision and perspective than most contemporary artists/scientists. This statement is no exaggeration because Kim Veltman spent 20 years studying Leonardo’s optical research, plus writings and drawings on perspective, as detailed in Leonardo’s notebooks; and Kim wrote several thousand pages on this topic alone.

The 6,500 pages of Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks contain ca. 100,000 sketches, diagrams, and drawings. Even today, we can learn much from Leonardo’s explicit explanations in his notes concerning the supremacy of visual images over verbal ones. Accordingly, we are engaged in a comprehensive study of Leonardo’s optical, perspective, and spatial methods—to probe his working techniques and to explain why Leonardo was so concerned with visual images.

As mentioned, Kim Veltman was a leading scholar of Leonardo da Vinci, and we shall publish all of Kim’s works on Leonardo in digital form. We are also working on the Encyclopedia of Leonardo da Vinci, which unites Kim Veltman’s writings on the great polymath. This outstanding multi-volume work explains Leonardo’s scientific methodology, optical studies, and perspective visualisation techniques.

Monograph and Dictionary of Perspective

In a strange quirk of fate, no book exists on the theoretical foundations of perspective (broadest sense); specifically to define, analyse, and unify all of the principles, types/forms, methods, instruments, and applications of visual/optical perspective. Henceforth, we are gathering everything known on this subject into a comprehensive monograph entitled The Art and Science of Perspective.

These books will be of interest to ‘vision-based’ professionals, including artists, photographers, filmmakers, cinematographers, architects, lighting designers, CAD engineers, VR/AR/MR plus digital metaverse content creators, 3-D/CGI/AI modellers, SFX/VFX creators, game designers, live/virtual/hybrid film production specialists.

In this book series, we wish to spark interest in visual and optical perspective, advance the subject by popularising it, and showcase the powers and capacities of related visual, imaging, and spatial concepts.

The monograph has eight planned volumes:

- Past, Present, and Future of Visual and Optical Perspective

- Dictionary of Perspective

- Natural and Visual Perspective

- Graphical and Mathematical Perspective

- Instrument Perspective

- Simulated Perspective and Illusion

- New Media Perspective

- Eyes: A User Manual

Our Dictionary of Perspective, is a standard lexicon of all terms on perspective, projection methods, vision, and spatial concepts. Hopefully, it becomes an instant classic and a cornerstone of knowledge for all ‘perspectivists’: with definitions of 3,200 terms and 1,200 types/forms of perspective, complete with synonyms, cross-referencing, etc, that enhances understanding of the definitions.

Research and Education

Perspective is a fast-developing field with many modern application areas predicated on perspective-related research and development activity. In truth, much is unknown, and many questions remain unaddressed. Ergo, research is ongoing across multiple disciplines concerning the principles, theories, types/forms, facets, phenomena, goals, functions, systems, instruments, and applications of visual/optical/technical perspective.

A significant problem for students and scholars of technical perspective, relates to the fact that the vast majority of historical perspective texts/treatises remain inaccessible because they exist in ancient versions of the Latin, Greek, Arabic, Indian, and Chinese languages, etc. Plus, many modern perspective texts are only available in various languages such as Italian, French, Spanish, German, etc. If perspective is ever to take its place as a stand-alone subject discipline, then it is essential to unite the field in terms of improving the accessibility of texts (as a minimum starting position); accordingly, at the PRC, we have begun the enormous task of translating key texts into the English language.

Perspective is such a vast, integral, and profoundly influential topic that it should be taught as a distinct subject in schools, colleges, and universities. Whereby perspective is the very definition of an interdisciplinary or cross-disciplinary subject, with countless sources, links, and fundamental relations that penetrate to the core of key phenomena in the arts, sciences, and technology. We aim to fill this evident knowledge gap with perspective category theory, educational papers, books, images, courses, lectures, vlogs and documentary films.

In sum, we are committed to educating young people about the fascinating history of perspective and the exciting possibilities this pivotal subject offers future generations.

Challenge of the Future

Perspective is an old subject with an exciting future. Today, the field of perspective is positively brimming with many new theories, methods, inventions, and vital application areas, and it continues to evolve rapidly.

Technological advances enabled by, or related to, perspective are numerous and mind-blowing. The various principles and methods of perspective lie behind many innovations; either explicitly in terms of optical instrument designs and visual operating procedures or implicitly in terms of the ways that images are processed, stored, networked/shared, viewed, and comprehended in a host of visual, optical, or digital ways.

Perspective transforms our concepts of space, time, vision, and representation. It is key for physical and mental orientation—and a tool for conceptual navigation, recording, and organisation of knowledge. Perspective has foundational links to almost every other subject discipline across the arts, sciences, and technology. Yet, the possibilities of perspective are still being explored. No wonder that perspective, which introduced the notion of an open horizon, is such an open field.

At the PRC, we explore the past, present and future of perspective. A key challenge is applying both old and new forms of perspective in auspicious ways, enabling us to visualise, model, and create a more humane world. In any case, the story of perspective has only just begun because it will shape our human future in such profound and varied ways that we can barely imagine the possibilities.

Patently, concerning perspective, there is much to do. Wish us luck!

-- < LATEST NEWS > --

Thank you for visiting the PRC website, which is under development.

We have planned 200 pages of information—and have completed around 85 pages thus far, so this project will take some time to complete. Indeed, progress is slow because we study perspective (all aspects) in great detail and record findings in our developing monograph: The Art and Science of Perspective.

---

-- < SCHEDULE > --

< SHORT TERM > :: Menu: STATE_OF_THE_ART :: Ongoing.

< SHORT TERM > :: Menu + Sub-Menus ::: THEMES :: Ongoing.

< SHORT TERM > :: Menu + Sub-Menus :: ACTIVITY :: Ongoing.

< SHORT TERM > :: Menus + Sub-Menus: PIONEERS :: Ongoing.

< SHORT TERM > :: Menus + Sub-Menus: GEOMETRY :: Ongoing.

< SHORT TERM > :: Menus + Sub-Menus: NEWS/NEWSLETTER :: Ongoing.

< MEDIUM TERM > :: Menu: MODULAR PERSPECTIVE :: Fall 2025.

< LONG TERM > :: Menus + Sub-Menus :: APPLICATIONS.

< LONG TERM > :: Menu::: GALLERY.

---

-- < PUBLICATIONS > --

The first two volumes of the Art and Science of Perspective, are to be published soon:

1. The Past, Present, and Future of Visual and Optical Perspective :: TBD.

2. The Dictionary of Perspective :: TBD.

---

-- < FREE DOWNLOADS > --

Download the Library of Perspective catalogue (with Veltman Archive) here:

Library of Perspective (catalogue) [60 MB pdf].

---

In relation to this website, please forgive any mistakes that creep into a project of this size and scope. Feel free to inform us of errors, falsehoods, etc., and/or suggest ways to improve the ideas presented.

Thank you, dear reader, for your kind patience.

And that's about it for now.

Alan Radley -- 11th November 2025 --

---

Dr Alan Radley FRSA | Scientific Director

alan@perspectiveresearchcentre.com

alansradley@gmail.com

Perspective Research Centre

www.perspectiveresearchcentre.com

You must be logged in to post a comment.