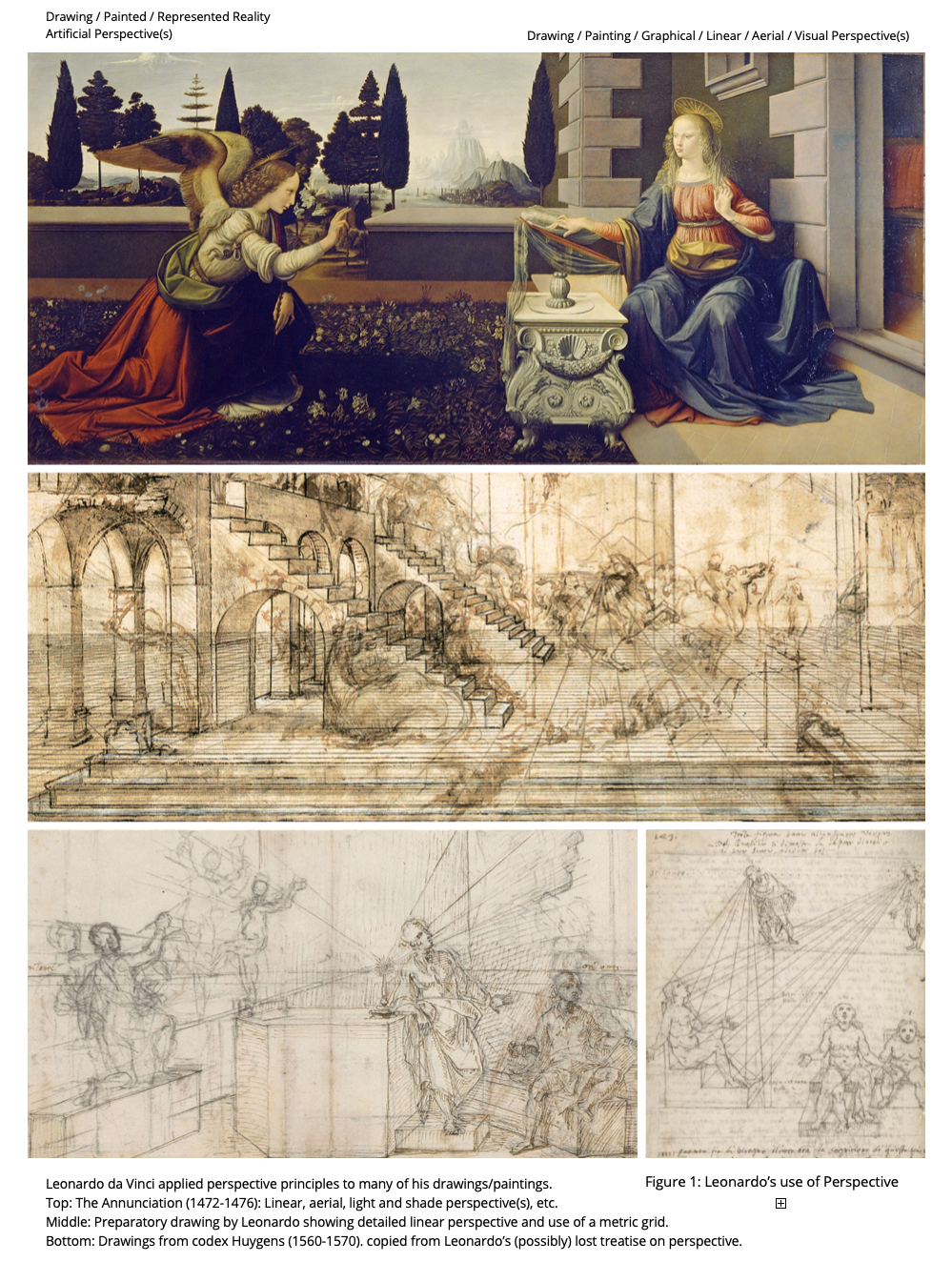

Italian scientist, artist, and inventor Leonardo da Vinci [1452-1519] developed a comprehensive theory of perspective that contains definitions, principles, and explanations that are remarkably modern in form.

Prior to Leonardo, Lorenzo Ghiberti [d. 1455], Leon Battista Alberti [d. 1472], and Piero della Francesca [d.1492] had written on perspective. But it was Leonardo himself who took discussions on this important subject to such a detailed and scientific conclusion that his theory of perspective remains of practical utility today.

Leonardo on Perspective

According to Leonardo, the laws of perspective are an inalienable condition of the perception of objects in space, and the eye sees objects in perspective automatically—because whenever it turns attention to a spatial scene; it sees the penetration by a transparent ‘perspective’ window of the so-called visual pyramid of rays, operating somewhat like an optical targeting system.

Leonardo goes on to explain fundamental axioms of perspective such as object/scene geometry, point-of-sight, picture plane or perspective window, and perspective phenomena such as aspect, diminution of size, diminution of form (loss of outline detail), and degradation of form, plus the formation of vanishing point(s)and a horizon line are also explained in detail, etc.

In his book on the ‘Art of Painting’ Leonardo says:

The art of perspective is to make what is flat appear in relief and what is in relief flat… and… all the problems of perspective are made clear by the five terms of mathematics; namely: the point, line, angle, plane and solid. ‘Perspective’ is nothing else than a thorough knowledge of the function of the eye; which simply consists in receiving in a pyramid the forms and colours of all the objects placed before it.

Perspective, according to Leonardo, is a rational demonstration applied to the consideration of how objects in front of the eye transmit their image to it, using a pyramid-of-lines; being the outer boundary of lines which, starting from the edges of the surface of each object, converge and meet at a single point (the eye). Leonardo explains that perspective in dealing with distances, employs two opposite ‘perspective’ pyramids:

The Pyramid of Vision; which has its apex in the eye, and the base as distant as the horizon; whereby each body is full of infinite points, and every point makes a ray… and rays proceeding from the points of the surface of bodies form pyramids (throughout space), and thus each body fills the surrounding air by means of these rays with infinite images, each body becoming the base of innumerable and infinite pyramids… and the point of each pyramid has in itself the whole image of its base… and… the centre-line of the pyramid is full of infinite points of other pyramids, also:

The Pyramid of Spacial Recession; which has its base towards the eye and the apex at the horizon; whereby objects of equal size, situated in various places, will be seen by different pyramids which will each be smaller in proportion as the object is farther off.

Whereby, the first pyramid includes the visible universe, embracing all objects that lie in front of the eye. And the second pyramid is extended to a spot that is smaller in proportion as it is farther from the eye, and this second pyramid results from the first.

Presciently and with great clarity, Leonardo has detailed the fundamental axioms of perspective, and he goes on to identify the basic types of perspective.

Natural, Artificial, Composite Perspective(s)

To begin, Leonardo identifies that perspective deals with the actions of lines-of-sight, and includes both the natural and artificial perspective categories in the subject. Natural perspective deals with optics as handed down by classical and mediaeval authors to Renaissance artists, and especially is understood by Leonardo to include theory from the ‘Optics’ book of Greek mathematician Euclid from 300 BCE who therein developed an explanation for the geometry of vision or visual perspective. Whilst artificial perspective is constructed geometrically/graphically as introduced by Renaissance architect Brunelleschi [1377-1446] around the year 1420 (i.e. linear perspective).

Leonardo defines visual perspective (or retinal perspective) as spatial objects/scenes seen by the eye at any distance. He equates this with natural perspective whereby, in geometrical terms, remote objects become proportionally (or optically) smaller with increasing distance. Leonardo also understood and widely employed the method of so-called artificial perspective or geometrical/mathematical perspective; being a drawing/painting made according to the strict rules of one-point linear perspective; and employing a planar perspective window intersecting the pyramid of vision.

In his notebooks, Leonardo made literally thousands of drawings in a perspective-like fashion; and many of these used the key method of linear perspective.

Leonardo also identifies composite or synthetic perspective which is a combination of perspective derived partly from art (graphics) and partly from nature (vision/optics). In this latter form of perspective, we may take into account that spatial objects/scenes viewed by natural perspective can differ (by design) from artificial perspective in distinct ways (e.g. by adjusting the geometry within a drawing to create a ‘synthetic’ perspective comprising elements of both kinds of perspective). One example identified by Leonardo is anamorphosis, for example when ‘wholly distorted’ drawings are projected by optical perspective methods into entirely different, but often realistically proportioned, image forms.

Leonardo himself was aware of a number of different kinds of discrepancies between visual/natural perspective and artificial or linear perspective.

For example, the eye deals with ‘visual angles’, or inherently measures the apparent angular size of an object (projected image angular extent onto a spherical retina); wheres perspective deals with projection onto a flat perspective window (represented on a picture plane). A spherical retina causes objects that subtend smaller visual angles, that is, identically sized objects located at the same distance along the optic axis, with each object located at a greater width/height laterally from the optic axis, to create correspondingly smaller images. This can be contrasted with the images formed formed by a (flat picture-plane) perspective method, which are all projected to identical sizes irrespective of width/height in the lateral direction from the optic axis.

Leonardo understood the aforementioned problem and also other discrepancies between the optical/graphical systems, but still accepted artificial perspective as a useful system, but one that must often be adjusted (within a drawing/painting) and to more closely match visual reality as experienced by the human visual system.

Both situations (‘natural’ or ‘visual’ perspective vs. linear or ‘artificial’ perspective) have a strict geometrical basis (the eye operates essentially as a pin-hole camera in terms of image/object magnification). If the human eye had a different form, for example with a planar (and non-moving) retina (instead of a spherical shaped retina), then such objects would all project onto the retina with an identical size, and the apparent contradiction between (perspective) planes and visual angles would not occur.

In sum, Leonardo identifies 3 classes of perspective:

- Natural Perspective: formation of an image of a spatial object/reality by optics and/or human vision.

- Artificial Perspective: formation of an image of a spatial object/reality by use of graphical construction.

- Composite or Synthetic Perspective: formation of an image of a spatial object/reality by using elements of both Natural and Artificial Perspective.

Leonardo makes the conclusion that no scene projected according to the rules of one-point linear perspective agrees completely with natural or visual perspective—and because image geometry discrepancies are always found (in one respect or another). Leonardo also introduces a fourth kind of perspective; namely true/measured perspective; which employs a flat perspective ‘veil or window’ to capture images from a real view/scene, a method that turns out to be somewhat similar to images formed by linear perspective (or a camera obscura / photographic camera), and also this method may be similar to that used by Brunelleschi to develop and test the first geometrically constructed linear perspective images.

Three Branches of Perspective

Leonardo defined perspective to refer to the combined reasons/effects for how the appearance of an object changes with increasing distance from the eye (plus changing angular direction relative to the eye’s central optical axis); ignoring distance-independent types such as parallel perspective. Today we might call these image distortion effects: perspective phenomena.

Leonardo identifies three branches (or facets) of natural perspective(or Receding Perspective) as:

- Perspective of Form [Type A: size/shape/angle/position]: includes aspect + diminution of size with depth.

- Perspective of Colour: the way colours vary as they recede from the eye/station-point (includes diminution of colour and contrast).

- Diminution of Form(Form Type B: 1,2,3,4) or the Perspective of Proportion [loss of outline structure] (aka., the perspective of disappearance): deals with how objects appear less finished in proportions as they recede from the eye/station-point (become less-defined in form/structure).

Leonardo cross-identifies three types of artificial perspective:

- Perspective of Form [Type A: size/shape/angle/position]: (aka. linear perspective): aspect + size reduction.

- Diminution and Loss of Colour: representation of colour changes at long distances due to aerial perspective (includes diminution and loss of contrast).

- Diminution of Form (Form Type B: 1,2,3,4) or Loss of Outline of opaque objects [loss of outline structure]: (ref. Perspective of proportion or the perspective of disappearance—representation of the diminishment of outline or loss of the visual distinctiveness of the forms at an increasing distance [perspective of visual acuity].

Elsewhere, Leonardo re-iterates his explanation; stating that (in both cases of natural/artificial perspective) the first division or Diminution of Magnitude/Size (geometrical / linear perspective) concerns the projected aspect and size of bodies (ref. Perspective of Form (Type A: size/shape/angle/position), and results from the structure of the eye combined with the relative geometry of the scene/observer; whereas the second and third are caused by the atmosphere and relate to aerial perspective (nominally ignoring scale).

Today we recognise/accept all of these basic perspective phenomena and noting that the third division, Diminution of Form (Type B: detail) or loss of outline, relates to not only aerial perspective (transmission and reflection of light rays as they pass through the atmosphere); but is also dependant on the detector resolution and visual acuity / focussing image blurring errors of the eye/camera.

Leonardo also identifies simple and complex perspectives; whereby simple perspective is a drawing made by the artist for an object shape/position equally distant from the eye in each of its parts; plus complex perspective (normal case) which is one made for an object shape/position in which not all of the parts are equally distant from the eye.

Figure 2: Perspectograph: Use of a glass, veil, perspective window, or perspective ‘net’, plus fixed eye-point, to make an accurate perspective drawing of an armillary sphere. Leonardo da Vinci, Codex Atlanticus, c. 1478-1519.

Degradation of Form (shape distortion)

Simply by employing/applying the above perspective types/concepts identified by Leonardo, plus by generating corresponding mathematical theory, we can create comprehensive scientific method(s) of perspective that can encompass most of the perspective representation and measurement problems faced by artists, architects, scientists, and computer graphics professionals even in modern times.

Using only basic axioms, Leonardo develops a sophisticated—and highly accurate/precise— perspective model complete with explanations of how/why spatial objects/scenes appear as they do under a wide range of circumstances.

For example, Leonardo can accurately explain degradation of form—being a composite set of visual effects that cause object outlines to (apparently) become distorted in shape (at a distance/angle) to varying degrees and in relation to specific geometrical and optical processes.

Leonardo identifies the basic object/scene degradation of form effects, and related Perspective Phenomena:

- Aspect of Form (visual angle): object shape as projected in the form of an image onto a picture surface (for various surface shapes/positions/angles).

- Diminishing Perspective: apparent object size recession and its (potential) effects on apparent object/scene shape with increasing distance (includes the generation of vanishing points and horizons, etc).

- Perspective of Proportion: apparent diminution and loss of outline distinctiveness (ref. aerial perspective and detector/eye spatial resolution).

Leonardo developed a sophisticated theory of geometrical optics, including illumination theory and the complex analysis of the perspective of light shadows/reflections/transmissions etc, which allowed him to paint several artistic masterpieces that today remain unmatched in terms of illusionistic realism.

Leonardo established close links between natural perspective (optical and retinal forms), and artificial (or one-point linear) perspective; and thus he was able to explain how the artist can mimic the appearance of natural scenes with great accuracy in drawings and paintings. Leonardo identified and explained (often for the first time in history) the origins of at least 15 basic types/forms of perspective—including depth-of-field visual effects etc, combined with dozens of related concepts.

Today we can construct highly accurate spatial views using the basic principles that Leonardo identified long ago as being part of the mathematical science of perspective; namely the: perspective of size, perspective of form (ref. the perspective of points, lines, angles, planes, and solids); and the perspective of proportion, plus the perspective of colour or aerial/atmospheric perspective.

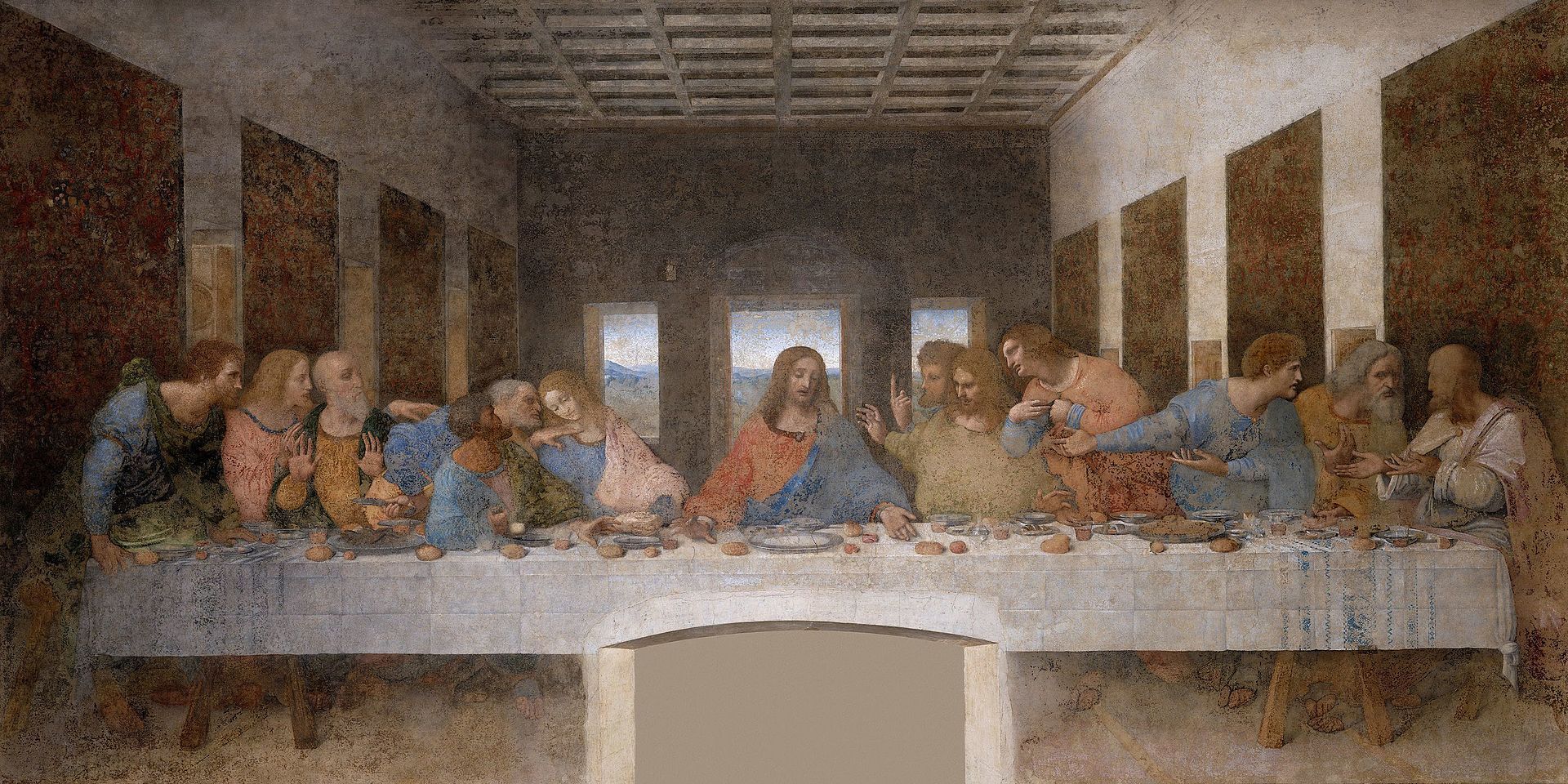

Figure 3: The Last Supper is a mural painting by the Italian High Renaissance artist Leonardo da Vinci, dated to c. 1495–1498. The painting demonstrates certain principles of one-point linear perspective; and also embodies a type of synthetic perspective whereby natural or visual perspective from the surrounding refectory where the monks eat has wall lines (sets of parallel lines) that appear to continue apparent perspective convergence into the painting being an artificial or graphical perspective using vanishing lines directed towards a central vanishing point.

Utility of Perspective

Leonardo believed that perspective was one of the most fundamental, practical, plus intellectually informative of all the various subject disciplines, and he stated that perspective demonstrated unrivalled utility throughout the arts and sciences. He also noted that perspective is by no means simple to understand and involves many long and drawn out proofs/explanations plus complex theory. Nevertheless, Leonardo placed such importance on perspective that he began writing an exhaustive treatise on this subject alone, and some parts of this work have come down to us through his book on painting.

Salient Leonardo quotations read as follows…

Perspective presides over all the functions and delights of the eye, with varied speculation…

These rules (of perspective) will enable you to have a free and sound judgement since good judgment is born of clear understanding, and clear understanding comes of reasons derived from sound rules, and sound rules are the issue of sound experience – the common mother of all the science and arts. Hence, bearing in mind the precepts of my rules, you will be able, merely by your amended judgement, to criticise and recognise everything that is out of proportion in a work, whether in the perspective or in the figures, or anything else.

Among all studies of the natural causes and reasons, Light chiefly delights the beholder; and among the great features of Mathematics the certainty of its demonstrations is what preeminently (tends to) elevate the mind of the investigator. Perspective, therefore, must be preferred to all the discourses and systems of human learning. In this branch [of science] the beam of light is explained on those methods of demonstration which form the glory not so much of Mathematics as of Physics and are graced with flowers of both. But the axioms (of perspective) are laid down at great length.

Those who are in love with practice without knowledge are like the sailor who gets into a ship without rudder or compass and who never can be certain where he is going. Practice must be grounded in sound theory, and to this Perspective is the guide and the gateway; and without this nothing can be done well in the matter of drawing.

In summary, in this short section on Leonardo da Vinci and perspective, we have only been able to introduce a small sampling of the great polymath’s work on this subject; and because he produced over 10,000 pages of notes and drawings that still exist today. Indeed almost every page either concerned perspective theory, or exemplified its principles.

Over the entrance to his school, Plato wrote: ‘Let no one ignorant of geometry enter here’. But for Leonardo the equivalent reads: ‘Perspective, therefore, must be preferred to all the discourses and systems of human learning.’ People often ponder on the source of Leonardo’s genius, but perhaps the answer lies in perspective, as he himself stated.

-- < ACKNOWLEDGMENTS > --

AUTHORS (PAGE / SECTION)

Alan Stuart Radley, 16th May 2025.

---

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Radley, A.S. (2023) 'Perspective Category Theory'. Published on the Perspective Research Centre (PRC) website 2020 - 2025.

Radley, A.S. (2025) Perspective Monograph: 'The Art and Science of Optical Perspective', book series in preparation.

Radley, A.S. (2020-2025) 'The Dictionary of Perspective', book in preparation. The dictionary began as a card index system of perspective related definitions in the 1980s; before being transferred to a dBASE-3 database system on an IBM PC (1990s). Later the dictionary was made available on the web on the SUMS system (2002-2020). The current edition of the dictionary is a complete re-write of earlier editions, and is not sourced from the earlier (and now lost) editions.

---

Copyright © 2020-25 Alan Stuart Radley.

All rights are reserved.

You must be logged in to post a comment.