Our journey into the multiple dimensions of perspective begins here.

We start by defining the scope of perspective topics to be examined. Next, we introduce perspective concepts and related terms to accurately delineate, explore accurately, and meticulously analyse the field of perspective (as a whole). Our goal is to establish perspective as a primary subject discipline, and accordingly, perspective category theory is developed.

Do not worry if said principles appear complex, highly technical, or daunting to commit to memory—because we shall return to these ideas—at a slower pace and in greater detail—many times on this site (and in related documents). Everything that follows is solely to clarify the emerging discipline of visual/optical perspective. Fingers crossed!

Concepts, Theory and Terminology

This website introduces basic elements of perspective category theory. Discussed are many old (and several new) concepts to map the field of perspective. Established ideas are employed wherever possible, but new facts/concepts require coining a new term plus definition. Indeed, most of what follows is novel theory, and you will not find these ideas anywhere else (apart from in related publications); at least this is so for the categorical analysis presented. Ergo, certain concepts are under development and subject to possible change as the theory develops.

Unfortunately, visual/optical perspective is a complex discipline, encompassing highly technical departments of visual knowledge. Ergo, it is not feasible to cover the entire subject on a website. Our focus is sampling the fundamentals of visual/optical perspective, whereas our monograph, the Art and Science of Perspective, develops a detailed exposition.

A note on terminology is salient. Within perspective literature, identical concepts have multiple names, and the same name is sometimes used for various concepts! In any case, we shall cross-reference all of these names in our Dictionary of Perspective, and settle on a standard term for each fact.

Nature of Perspective

We begin by asking for a concrete definition of perspective.

Unfortunately, the task of answering this question is fraught with difficulties. Thousands of articles, books, theses, and treatises have been written to tackle the puzzling complications that arise in this respect. Perspective is one of the most fundamental, theoretically challenging, perplexing, yet elusive topics.

But why is perspective such a challenging topic? This is partly because many different types of perspective are known. We have visual, mathematical, and graphical perspective, etc. Secondly, multiple types of perspective tend to operate simultaneously, so it is difficult to identify the root causes of specific visual effects.

As a result, perspective is an inherently complex topic. Anyone who seeks a deeper understanding of perspective has to engage the old noggin, as my father used to say. But how can we deal with such complexity? Perhaps only by defining all classes of perspective, identifying the salient features of each type, before characterising the particular circumstances that bring each form into play.

We must open our eyes to all of the varied dimensions of perspective!

The Categories of Perspective

In the Oxford English Dictionary (2nd Ed.), perspective is variously defined as the science of optics, an optical instrument, the art of representing objects in a 3-D space, a drawing or picture, a visible scene, and the act of looking, etc.

Accordingly, we can define perspective, in general terms, as the formation of an image—or a representational pattern—of a state of affairs present in a spatial reality (e.g. physical, illusive, imagined space, etc). Perspective may refer to the process or procedure (ref. system category) that produces said image (e.g. graphical perspective method), or it may refer to the result, the visual image form itself (e.g. a perspective drawing).

An image may be either of the visual type to reflect visual features of an object/scene, or be of the non-visual type and reflect non-visual characteristics (ostensibly). Accordingly, there are two main classes of perspective: visual perspective and symbolic perspective (non-visual perspective), which correspond to the two basic kinds of images: visual and non-visual Images.

As the name suggests, visual perspective (of the first type, or not overtly related to the human visual system) refers to when a visual image is used to view, match or represent the visual appearance of a spatial object/scene. Alternatively, symbolic or non-visual perspective deals with non-visual images (e.g., literal, logical, ontological, or algebraic images). Noteworthy is that for the non-visual class of perspective, the ‘images’ formed may relate to spatial/visual features or other non-visual features of the object in question.

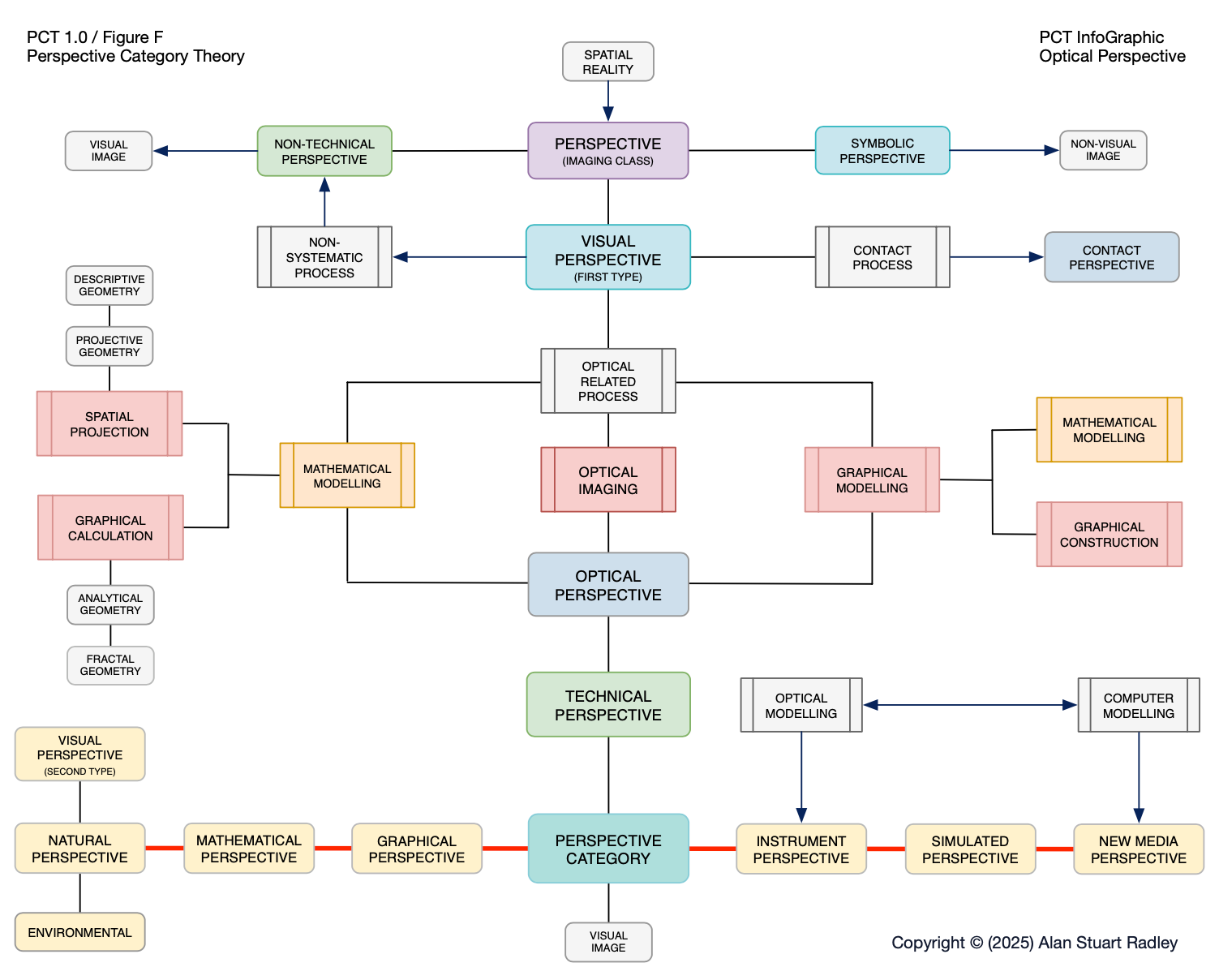

Figure 1 shows the categories of perspective and details processes that give rise to one class of visual perspective, namely optical perspective. Note that several other kinds of visual perspective are missing from this diagram, including sonar (sound ‘imagery’), magnetic, mechanical, gravitational perspective(s), etc.

Without realising, we are building a class hierarchy or taxonomic tree of perspective. It is noteworthy that classes are often overloaded on said tree, whereby one class of perspective is the daughter of a higher-level class. For example, we have technical perspective, a type of optical perspective, which is, in turn, a type of visual perspective (ref. one branch of the class tree structure).

As our discussion continues, we shall build our knowledge of the lower-level classes, particularly those under the optical perspective branch.

Visual and Non-Visual Images

The reader may find the inclusion of the symbolic or non-visual class of images—and associated perspective forms—a little surprising. At least when defined alongside perspective proper (the visual, graphical perspective types, etc). Still, non-visual images are fundamental throughout literature, science, culture, etc.

A word image can build up a picture of a spatial object/scene using purely language-based descriptions, whereby the result is sometimes identical to a visual image. This can happen by metaphor, descriptive methods, or mathematical formulas. For example, the ‘visual image’ of a three-dimensional cube of a specific size and colour can be produced by either image class.

Nevertheless, it is usually the case that visual and word images of the same spatial object/scene, will differ significantly. Shape, fine details, surface contours, spatial relations, optical effects, etc., are often more accurately captured with visual images. Alternatively, non-visual images can convey hidden or difficult-to-see facets missed by visual methods. Said features include chemical and atomic makeup, invisible forces at play, and other invisible facets, such as micro-processes, etc.

We can make an interesting distinction between permanently and temporarily invisible features. For example, it is sometimes the case that previously invisible features of an object/scene become visible when viewed using the correct perspective or using an appropriate viewpoint, scale, timescale, etc.

Contact Perspective

Contact perspective refers to the direct mapping of spatial form, namely a spatial object/scene, and by utilising physical contact using one, two or three-dimensional examination procedures (1-D/2-D/3-D space). Contact perspective is perhaps the purest—or most ‘real’ class of perspective—because it deals with the physical world in its actuality.

We can identify two different kinds of contact perspective:

- Handling perspective – scales, rulers, callipers, sensors/actuators, etc.

- Moulding perspective – casting processes, projection moulding machines, etc.

It is difficult to argue with (or contradict) data that arises from direct contact with the object of attention, at least in scientific or materialist terms. However, it is essential to realise that many of the same data-gathering tasks arise with both contact and optical perspective. For example, the problem of determining true object shape versus apparent and/or partial object shape.

Note that we have included specific perspective-related handling and calculating methods within our perspective category theory, namely scales, rules, callipers, slide rules, etc., as falling under instrument perspective. Ergo, all measuring/calculating devices are classified under the technical, optical perspective branch. We have done so to simplify the classification scheme. Such devices often involve using human vision to take readings or apply said methods to physical reality.

In sum, the various kinds of contact perspective have strong links to the other types of visual perspective; and they have been widely used to develop, validate and certify mathematical, graphical, instrument, and new media types of perspective.

Optical Perspective

Optical perspective involves capturing, measuring, or representing realistic views/images of dimensional space. Optical perspective encompasses all forms of perspective that use, or purport to use, light, or electromagnetic radiation, to analyse/represent a spatial scene; including all wavelength ranges from gamma rays, x-rays, visual spectrum, microwaves, radio, etc.

Some forms of optical perspective employ artificial/simulated ‘light-rays’ that lie beyond the bounds of ordinary physics. Said techniques can sometimes operate on an impossibly vast or tiny visual scale; or produce images that pass straight through solid objects, etc. However, the use of such techniques does not necessarily make the resultant visual images any less real or accurate (ref. heavenly, sub-atomic and medical optics, Virtual Reality, etc).

Noteworthy is that we have adopted the term optical or technical perspective for a broader range of meanings than purely ‘optical’ phenomena such as photography (for example). Included in that term is any systematic optical-related process that produces visual images (of any type) concerning spatial reality.

As we shall learn, there are many different categories of optical perspective. Still, all involve spatial imaging principles that reflect scene geometry aspects with varying degrees of visual realism or accuracy.

Optical Model of Spatial Reality

Another way of characterising a visual image produced by optical perspective, is as an optical model of spatial reality (existing or imaginary). How so?

Well, a perspective image is typically a two-dimensional representation (or projection) of structure in a three-dimensional world, a simplified or idealised conception of that world. The same image faithfully reflects, generally on a smaller scale, aspects of the existing structure to function as a compass (for a particular extent of prescribed space). In this manner, the perspective image becomes a map (or model) of the external spatial reality. Often, the model is put forward as a basis for perceptions, calculations, predictions, or further investigation.

However, if the perspective image is a model, it stands to reason that it results from modelling procedures. In this respect, we consider an optical instrument that produces sufficiently accurate perspective images in form, detail, etc., a modelling process for the projected spatial reality.

In light of this discussion, optical perspective is the production of an optical model (or visual image) that is the outcome of a systemic optical process comprised of a set of imaging and/or optical-related modelling procedures.

We have identified five optical processes that produce perspective images:

- Optical Imaging – environmental optics, eyes/vision, optical instruments, etc.

- Mathematical Modelling – Analytical, Descriptive, and Projective Geometry.

- Graphical Modelling – artistic drawing, painting, CGI, etc.

- Optical Modelling – geometrical optics, ray-tracing, image processing, etc.

- Computer Modelling – GIS, GPS, Virtual Reality, hypermedia, etc.

We have defined optical perspective to operate wherever a real, simulated, or modelled optical view/image of a spatial reality is produced (by whatever method).

It is worth noting that the aforementioned optical-related processes are by no means independent of one another. It is often the case that several different modelling processes are involved in producing a particular perspective image. For example, movie/cinema computer-generated imagery (CGI) typically involves mathematical, graphical, optical, and computer modelling simultaneously.

Now that we have adequately delimited our primary subject matter, we can explore perspective category theory in detail.

Perspective Category Theory

We adopt a scientific, logical approach to the field of perspective.

Some people may object to applying scientific principles since perspective is both an art and a science. However, doing so has many advantages, most notably because we can establish concepts and principles upon which the entire field of perspective is built.

Perspective sometimes deals with unreal, imaginative, and illusionistic three-dimensional spaces. However, these same spaces are often visualised, or represented using realistic ‘looking’ or ‘material’ copies of the same visual images (or perspective proper). Henceforth, visual realism is a key component of all perspective forms (ref. technical forms).

Desired is a new perspective category theory, which hopefully can be used to understand, model, and apply complex perspective phenomena in the broadest range of practical circumstances. The first step in building a theory is to identify a group of concepts—or set of matching universal forms—that purports to represent all of the different facets of perspective.

The sections below introduce key principles upon which perspective category theory is built. Most of these concepts can be explicitly/theoretically proven, but if not, then said principles can hopefully be demonstrated empirically.

The Optical, Visual, and Represented World(s)

Optical perspective seeks to view, match, or represent aspects of the optical world—or the changing appearance of objects as conveyed to the camera, instrument, or the eye/detector by emitted or reflected light (ref. using real, modelled, represented or imaginary light-rays). Ergo, a key goal of perspective is to explore the physical world by using the optical world to probe spatial reality accurately or with sufficient realism.

The natural products of human vision are named as the visual world (unaided eyesight)—or the transformation of the optical world according to the rules/processes of human vision (ref. physiological and psychological optics). In addition, the represented world refers to human attempts to depict aspects of the physical, optical or visual world(s).

Finally, we have perspective illusions or the Illusive optical world, which makes false impressions of size, location, depth, position, or transparency concerning a spatial scene/object. These are produced by natural and human-made methods and by utilising optical phenomena plus optical arrangements, such as mirrors, holograms, etc., or computer-generated Virtual or Augmented Reality systems.

The physical, optical, visual, represented and illusive worlds possess fundamental mapping relations. However (as we shall learn), the precise nature and validity of such correlations are by no means straightforward or guaranteed. Ergo, a secondary goal of optical perspective (greatest sense) is to understand how the different facets of each world fit together to produce visual reality.

Optical perspective can be separated into the technical and non-technical categories of perspective—as explained below.

Technical Perspective

Technical perspective refers to any systematic process that produces a detailed visual image, measurement, representation, model or view, of a three-dimensional object or scene. Technical perspective is formed using optically, mathematically, geometrically, or logically correct/known/consistent principles.

Technical perspective can be separated into distinct categories and sub-categories. Still, importantly, all types of technical perspective are recognised by having a direct connection to human vision, environmental optics, and/or related visual processes/methods or associated instruments/machines.

Technical perspective includes all naturally occurring optical effects that can be classified under optics of the environment, including, for example, optics of the heavens (sun, moon, stars, etc), shadow projection, panoramic views from mountain tops, underwater optics, etc. Also classified under the heading of technical perspective is the vision of all animals, including human vision and birds, frogs, fish, insect eyes, etc (named as visual perspective of the second type).

It is essential to realise that most types of representation (including visual illusions) are included in the technical class. Specifically, this is so—wherever said effect relates to the ordinary laws of environmental optics or the expected results of human vision (ref. physical and psychological optics).

Non-Technical Perspective

Non-technical perspective is any non-systematic process producing a detailed visual image, representation, model or view of a three-dimensional object or scene. Non-technical perspective does not involve the application of a comprehensive visual theory/process/method of image formation or optical projection. Non-technical perspective is formed using optically, mathematically, geometrically, or logically incorrect/unknown/inconsistent principles (including nonphysical processes).

Examples of subjects that are normally classified under non-technical perspective include aperspective, axial, inverted, negative, time (random combinations of images taken at different epochs), freehand drawing, birds’ eye, etc. Whereby a non-technical perspective category is recognised by evident non-connection to the ordinary laws of optics, or because it fails to match the expected results of human vision. Non-technical perspective includes graphical methods that today are classified as ancient perspective (e.g. aspective or Egyptian perspective or Byzantine perspective [reverse/inverse/inverted perspective]).

The first systematic or technical perspective ever developed is usually agreed to be Renaissance perspective (i.e. central, scientific or linear perspective). Today, other forms of technical perspective are known; such as parallel, oblique, 6-point, and many different kinds of optical projection, including mapping projections of the earth and heavens, etc.

Natural Perspective

Natural perspective is any naturally occurring instrument/process that produces a detailed visual image, view or shadow/outline of a three-dimensional object or scene. Natural perspective includes visual perspective (second type) or human and animal vision (eyes).

Environmental perspective is a natural perspective that refers to naturally occurring optical effects such as projection of shadows/outlines, line-of-sight problems, translucency/reflection/colour effects, etc., that happen in the natural environment (and without human interference). For example, astronomical, atmospheric, underwater optics, optics of crystals, rainbows, etc. Noteworthy is that all forms of architectural buildings (and associated optical vistas) are herein classed as a form of environmental perspective.

Categories of Perspective

The primary categories of visual/optical/ technical perspective are listed below and encompass most perspective methods employed in modern times.

Visual/optical/technical perspective has six primary categories:

- Natural perspective (views of natural and built worlds) – including visual perspective (second type) or direct looking at spatial reality using human or animal vision (view of a three-dimensional form/scene), also includes environmental perspective;

- Mathematical perspective (views of natural and built worlds) – modelling spatial reality and/or shaping appearance(s); includes the second mathematical type or geometrical perspective, and also the third type dealing with optical projections (projection perspective);

- Graphical perspective (views of natural and built worlds) – copying spatial reality / creating appearance(s) or representations of reality;

- Instrument perspective (views of natural and built worlds) – looking at, capturing and measuring spatial reality; and projecting appearance(s);

- Simulated perspective – aka ‘false’ or ‘trick’ perspective (designed views of natural built worlds) – visual illusion by the construction of a false spatial reality, or by the representation of a false spatial reality (distorted/transposed scene geometry);

- New media perspective (views of natural and built worlds) – connecting/linking, ordering, constructing (mimesis), matching, mixing, exploring, and cross-matching: multiple perspective view(s).

We shall explore the six categories of technical perspective in detail throughout this site. Hundreds of perspective sub-categories (and forms) fall under these six headings.

Note that the form of visual perspective listed under the natural perspective category is identified as the second type of visual perspective; which relates directly to human vision. This form is contrasted with the first form of visual perspective, existing at the top of the perspective taxonomic tree, under which all classes/categories of optical perspective are contained.

Goals / Products / Functions of Perspective

A perspective image is a visual image formed by a category of optical perspective that works to view, match, represent, and make an illusion of, or an apparent immersion into, spatial reality.

Goals of optical perspective <IMAGING CLASS>:

- View: look at a spatial reality—capture/prescribe/observe perspective images of a 3-D scene.

- Match: measure a spatial reality—figure/survey/classify/match/cross-match

perspective images of a 3-D scene. - Represent: copy a spatial reality—model/index/link/mix/explore perspective

images of a 3-D scene. - Illusion/Immersion: false impression of viewer place, false object dimensionality: size, depth, transparency, etc.

The five goals of perspective relate to specific outcomes tied to generating perspective image(s), of one kind or another. Each goal may be met by a system of perspective that embodies the categories/forms of perspective, with corresponding perspective phenomena, and utilising one or more principles/ methods of perspective.

As stated, technical perspective falls under the heading of optical perspective, and is any optical process that forms a detailed visual image, measurement, representation, model, or view, of a 3-D object or scene (ostensibly). These outcomes relate to the products of perspective; or attaining subsumptive data (whole/part), ordinal data (figure/size/scale/position) and/or determinative data (state/activity) from a perspective image and in relation to a spatial reality.

Perspective unlocks a whole universe of visual complexity. The various classes of technical perspective can produce an exceptionally diverse range of visual images/views. Perspective generally works to capture, observe, prescribe, measure, classify, model, survey, map, index, gauging, certify, link, mix, explore, display, and project perspective images of the physical world. These are the functions of perspective (or partial subset of the same).

By now, the reader will be aware that the field of visual/optical/technical perspective is highly complex; and further that everyday perspective scenarios—such as a person watching a movie or television program, or else looking at a painting or photograph, are examples of perspective processes that can only be fully understood by using strict logical definitions/concepts, including appropriate application of perspective principles, facts, methods, and associated theory, etc.

Perspective Phenomena

Perspective phenomena refer to apparent and generalised changes to object/scene visual features that occur according to a particular type of perspective and its inherent processes. One example is foreshortening; whereby we have two types/components: the geometrical or axonometric class, and the optical or perspectival class.

It is important to note that not all forms of graphical perspective employ/exhibit every single type of perspective phenomenon. Parallel perspective (for example) uses only aspect of form (axonometric foreshortening) but not diminution of size, perspectival/optical foreshortening, horizon line, or vanishing points.

Perspective Principle / Method

A perspective principle refers to an imaging mechanism, composable into a perspective operation consisting of (at a minimum) real/modelled scene/object and picture-plane/surface structures, plus one or more <OPTICAL>, <MATHEMATICAL>, <GRAPHICAL>, <COMPUTER> process(es), working to produce a visual representation which reflects certain aspect(s) of a spatial reality.

A perspective method is any imaging technique that works to instantiate one or more perspective principle(s), resulting in a detailed visual image, measurement, representation, model, view, or projection, of a 3-D object or 3-D scene. Typically one or more such methods are combined to render a view/image/ measurement/model according to a particular category of technical perspective.

Formerly, a perspective method is encapsulated in perspective principles (imaging mechanisms), mathematical formulae, theoretical or practical technique(s), etc., and typically consists of physical, optical, or information-processing structures/processes applied systematically to a 3-D scene. The instantiation of such structures/processes can happen naturally due to image formation in a human eye, or they can be applied using an instrument, computer, or graphical technique (for example, the principle(s) of linear perspective, etc).

System Category

A perspective system is a particular scheme of visual/optical/technical perspective that operates as a unit of perspectival image-making capability, image-projecting capability, or image-analysis/matching functionality. The perspective system may be comprised of one or more categories of perspective, operating with corresponding principles and methods of perspective.

A salient example of a perspective system is a person in a cinema theatre watching a movie. Whereby we have multiple types of perspective contributing to the overall visual experience. First, we have production of the movie using a combination of natural/environmental plus camera or instrument perspective(s). Next, we have instrument perspective from the projector in the cinema, and finally, visual perspective when the viewer looks at the movie screen images. Therefore we have several interoperating perspective systems/categories that produce a corresponding set of visual transformations for the resultant perspective images. In this case, the ‘image-chain’ passes from camera, projector, to human-eye, and the entire procedure is considered to be a single perspective system.

Notice how perspective category theory helps us to identify which types of perspective principles, methods, and phenomena are evident in a practical situation. However, consider that the linear perspective form is both a kind of mathematical and graphical perspective simultaneously. Hence, a particular perspective image/ view may fall under multiple categories (and be shaped accordingly). Another factor to consider is the psychological dimensions of visual perspective, which can strongly affect the perception of views/images.

The aforementioned perspective elements help us to break down what would otherwise be a highly complex (and often obscured) group of optical/geometrical/perceptual processes. Ergo, perspective category theory allows us to identify and separate technical perspective into an eminently manageable set of readily identifiable perspective categories, image forms, principles, phenomena, methods, systems, etc.

Perspective Model

A perspective model is a perspective system that enables building of a comprehensive three-dimensional visual representation of a spatial reality.

A virtual perspective model is a Computer Graphic (CG) copy of the overall form/structure of, plus material/optical processes within, a spatial reality; it includes mathematical modelling to accurately represent complex visual facets. Correct scaling, proportions, and arrangement of linked images form a coherent, unified, often interactive, copy of a spatial reality. Often, accurate multi-view/multi-scale/multi-time images/views may be created in relation to mapped object/scene facets. Examples of virtual perspective models include CAD, CGI, CV, GIS systems, Virtual, Extended, Augmented Reality, etc.

Perspective Direction

Optical perspective produces visual images of a spatial reality; we have two basic classes of perspective image, or perspective directions; as listed below.

- Captured perspective Image <IMAGING FORM>: formation of an image or representation ‘backwards’ from a spatial reality.

- Projected perspective Image/Beam <PROJECTED FORM>: sending images ‘forwards’ into a physical reality, or projecting light-pencils/shadows onto physical objects (2-D or 3-D).

A captured perspective image refers to the formation of ‘optical’ images ‘backwards’ from a spatial reality onto an image or picture plane/surface, or that results from generation of a perspective representation of the visual appearance of a spatial object/scene (ref. viewpoint geometries). Captured perspective images include perspective drawings, paintings, computer graphics, and images formed by optical instruments such as eyes, lenses, cameras, telescopes, etc. Such images include certain kinds of simulated, mathematical, non-real or purely modelled images such as those produced by mathematical modelling, CGI, and computer ray-tracing images, etc. The key point is that a captured perspective image is a 2-D or 3-D representation of a 3-D spatial reality produced according to the rules of one or multiple kinds of visual/optical/technical perspective.

A projected perspective image or projected light beam is the projection of an image/light-beam/pencil/shadow ‘forwards’ into a 3-D spatial reality (image is overlaid onto spatial scene/objects)—and in such a manner that the same reality is altered in a visually apparent way. Examples are images formed by Virtual/Augmented/Mixed/Extended Reality, holograms, cinema projectors, light-beams, and shadows cast by lights, candles, sun, etc.

Oftentimes, a perspective method combines captured and projected perspective images into a single system (e.g. cinema, holograms, VR). We can conclude that optical perspective deals with viewpoint and light-ray geometries relating to a spatial reality of one kind or another—and it involves optical imaging/projection, or producing captured and/or projected perspective images/views/light-pencils/light-beams/shadows. Patently, optical perspective(s) come in a variety of types; and our task (as humans embedded in physical reality) is to understand why/when/where/how each form is embodied—and thus to ‘decode’ optical reality.

Geometrical Image Form

Typically, each type of optical perspective image is produced by one or more perspective categories that relate to the optical/mathematical/graphical/computer processes involved. Whereby a geometrical image form is the visual image shape outcome(s) of said process [visual contents of image], and refers to the overall (apparently transformed) geometry of a spatial object/scene; including (for example) the number and position of any vanishing points, horizon lines, etc.

The geometrical image form is also known as the perspective form, for example, a one-point linear perspective image may be referred to as a linear perspective form (produced by a particular category or system of perspective, for example, the one-point graphical perspective construction method).

Optical Image Form

An optical image form refers to the overall (possibly transformed) light ray intensity/wavelength detected features or colour/contrast facets of a perspective image/view. The optical image form is (largely) independent of geometric structure, but relates to colour, illumination, and shading features present in object space, and hence to the purely optical contents of the perspective image (including light ray properties such as wavelength and intensity).

Normally, the term perspective form refers solely to the geometrical image form and not (at least solely) to the optical image form.

Media Image Form

A different nomenclature describes the containing media for said image; the media image form. For example, a perspective drawing will have either a physical, digital, or virtual embodiment (media image form), combined with a particular set of visual features and image appearance transformations (geometrical image form) or perspective phenomena (e.g., pen/ink drawing on paper). Said phenomena may affect the appearance of object outline structure for example.

Various image instantiations (media forms) are possible for each category. For example, graphical perspective can manifest itself in different kinds of linear perspective image, such as in a drawing, painting, animated or computer-generated image, VR system, etc. Whereby each instantiation of a perspective image form may differ significantly or subtly from others (in terms of media image form [container] and/or geometrical image form [contents]); even for a notionally identical spatial object in the same spatial scene.

Definition Problems

Perspective is a complex topic, one that is beset by problems related to establishing accurate, precise, consistent, and widely accepted concept definitions.

Such problems arise because experts have employed different terms for the same concept or used an identical term for differing concepts, etc. These problems are compounded because people employ the term ‘perspective’ imprecisely and alternately for both perspective method(s) and outcome(s). We have attempted to sidestep these problems using overt concept definitions, but ambiguities and issues remain as explained below.

Categorical Ambiguity and Overloading

A perspective category refers to a specific class of perspective system; with a corresponding set of optical, mathematical, graphical, instrument/illusive, or new-media processes. Oftentimes, more than one category is involved simultaneously to produce a perspective view/image; which is a form of categorical ambiguity, involving composite perspective (multiple categories used in direct succession); or category chaining, such as when we use a camera (instrument perspective) to photograph a natural scene (natural perspective).

Sometimes, the same sub-class can appear under multiple top-level categories; named category overloading, for example, when we have a linear perspective drawing, which seems to be equally a graphical and mathematical perspective category simultaneously.

Combined Category and Form Ambiguity

Sometimes a perspective type appears to be both a perspective category and perspective form (geometrical image form). This situation is called a category/form ambiguity. But why is this so? The answer is that (for example) linear perspective is a name that applies to both a perspective category (a method/process) and a perspective geometrical image form simultaneously. This may seem a little confusing, but if we consider that optical perspective is defined as an image-making process, then it becomes clear that we can refer either to the process and/or outcome(s) as required (and further that these may be inextricably linked or related in mathematical/optical terms).

Our scheme clarifies the multiple and sometimes confusing usage of perspective terms. This is evident with linear perspective, which has many variants/doppelgangers: firstly, with different (process) categories, including the graphical, photographic categories, etc., and secondly, different (transformed image) perspective geometric forms, or outline structural forms, such as one-point, two-point, three-point perspective images, etc.

Types of Space

Perspective seeks to reflect visual aspects of the physical world (typically).

Perspective is concerned with obtaining views of a spatial reality, and it deals with transformation of one kind of space to another kind of space. Whereby perspective happens when a three-dimensional object located in three-dimensional object space (real, virtual, or imaginary) is transformed into a two or three-dimensional image located in a two or three-dimensional image space (real or virtual).

Perspective remains a complex topic because it involves the comparison of fundamentally different categories of space. For example, reconciliation of the 3-D space of the physical world (physical space), with the 2-D space of graphical perspective (graphical space). Often, and despite a strong desire to attempt equality, this reconciliation is impossible to achieve completely; because one deals with dimensions that must map without any physically-based 1:1 correspondence (e.g. transform 3-D space to a 2-D space).

It is essential to realise that one kind of perspective typically involves multiple types of space. Let us take the example of a person looking at a painting of distant mountains (the so-called target space). The viewer creates a visual space using pictorial elements perceived from a graphical space (the painting), including an inherent mathematical space expressed by the artist as a linear perspective projection. The overall effect is an apparent (or illusionistic) view of a natural or physical space (ref. the target space or environmental perspective of the same).

The upshot is that anyone who wishes to apply perspective to a visual problem has to decide first which categories of space are involved, before identifying which perspective categories, principles, methods, forms, and phenomena are operating, and to understand the generated perspective image product(s). Ergo understanding the different categories of space, and operating processes of perspective, is of central importance if we wish to explain how and why the optical, visual and represented worlds appear as they do.

Perspective Instruments

Our discussions thus far have side-stepped an essential aspect of perspective: the use of instruments and machines to view, image, measure, model, and represent visual aspects of the physical world. An instrument perspective; is generated whenever an instrument, of one type or another, is used to view, capture, measure, or project an image of a scene.

For image capture, we have cameras, telescopes, microscopes, etc. Other instruments have been developed for image projection and display. In this respect, many innovations have occurred, ranging from the earliest such as the magic lantern and kinetoscope to modern cinema techniques, such as wide-screen and 3-D cinema, computer, television and mobile screens, plus immersive systems, including IMAX theatres.

Today we have new types of digital media and networked computing devices, including smartphones and tablets, which can display and manipulate a variety of perspective views. However, it is essential to realise that perspective instruments and machines are conceptualised, built, and operated, according to mathematically, geometrically, and logically consistent principles (hopefully). In other words, all such devices are enabled by valid perspective theory/methods.

Patently, perspective instruments and machines have the potential to add further complexity to the already complex perspective topic. However, we should not be worried because often perspective instruments can simplify, expedite and clarify matters. This happens because perspective devices give us new choices regarding what we see, how, when, and where. In the process, we magnify our natural visual capacities and boost the efficiency, number, and usefulness of perspective images and techniques, measurements, models, etc.

Advantages and Limitations of Category Theory

Using technical perspective, we can approach objects from different viewpoints and scales, leading to distinct visual/geometrical functions that can be isolated, catalogued, and explored. By clearly identifying perspective categories, we can analyse and (hopefully) explain the precise origins of perspective phenomena and better understand/manage attendant physical processes.

Let us take the example of a person looking at a painting of distant mountains. The viewer uses eyesight (visual perspective) to perceive pictorial elements from a graphical space (the painting), including an inherent mathematical perspective expressed by the artist as (for example) a linear perspective projection. The overall effect is an apparent (or illusionistic) perspective view of a three-dimensional natural scene (ref. natural or environmental perspective).

Notice how perspective category theory helps us to name which types of perspective phenomena operate in a practical situation. However, notice that linear perspective is simultaneously a form of mathematical and graphical perspective. Hence a particular perspective image/view may fall under one or more categories. Most types of perspective involve mathematical principles, or mathematical perspective, to one degree or another. Similarly, all kinds of visual perspective (2nd type) involve environmental perspective, etc.

Another vital factor to consider, which complicates matters further, is the psychological dimensions of visual perspective, which refers to the operations of the human mind on the perception of perspective images/views. The implications of the latter topic in our discussion are important and complex and must be adequately considered.

In any case, and especially considering the multi-variant nature of perspective, the categories above help us break down what would otherwise be a highly complex (and often obscured) group of optical/geometrical/perceptual processes. Ergo, perspective category theory helps us to identify and separate technical perspective into an eminently manageable set of more straightforward and readily identifiable phenomena.

Conclusion

We have now concluded an introduction to a novel approach to the field of perspective; previewing facts/concepts employed throughout this site.

The founding principles of perspective category theory have been introduced, even if we have not yet explored all explanations, problems/solutions, and implications thereof. Unfortunately, despite the apparent complexity of this exposition, this is not the end of the story when it comes to unifying the vast field of perspective. We must build a complete catalogue of all classes/branches of perspective.

Overall, perspective is the preeminent way for humans to image, view, match, and represent a whole universe of visual complexity. Perspective has a fascinating past, exciting present, and promising future. By utilising advanced perspective methods/instruments, we vastly expand the field/range/depth of human vision. And given the amazing triumphs provided by the remarkable history of perspective, who can say what incredible heights perspective can take humanity to?

Prepare yourself for an invigorating ride as we embark on a fascinating journey into the marvellous and varied world(s) of perspective!

-- < ACKNOWLEDGMENTS > --

AUTHORS (PAGE / SECTION)

Alan Stuart Radley, April 2020 - 1st June 2025.

---

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Radley, A.S. (2023-2025) 'Perspective Category Theory'. Published on the Perspective Research Centre (PRC) website 2020 - 2025.

Radley, A.S. (2025) Perspective Monograph: 'The Art and Science of Optical Perspective', series of book(s) in preparation.

Radley, A.S. (2020-2025) the 'Dictionary of Perspective', book in preparation. The dictionary began as a card index system of perspective related definitions in the 1980s; before being transferred to a dBASE-3 database system on an IBM PC (1990s). Later the dictionary was made available on the web on the SUMS system (2002-2020). The current edition of the dictionary is a complete re-write of earlier editions, and is not sourced from the earlier (and now lost) editions.

---

Copyright © 2020-25 Alan Stuart Radley.

All rights are reserved.

You must be logged in to post a comment.