Perspective phenomena are how light rays, real and simulated, emanating from a light source or reflected from a surface, fall upon, or are imaged onto, a picture surface, screen, or real-world object/scene; to form patterns that can help us to make judgements about the structure and material constituents of a spatial scene.

Perspective phenomena determine how a spatial object/scene appears from a particular viewpoint <IMAGING FORM>; or how a scene’s illumination/shading changes according to structure or alters due to light sources, reflections, surface features, occluding objects, etc., present within the scene <PROJECTION FORM>.

Let us now explore perspective phenomena and how they arise.

Classes of Perspective Phenomena

Perspective phenomena refer to all of the object/scene visual appearance factors, actually present in (or in some cases absent from) a perspective image, and that (potentially) provide clues and information about the geometrical structure, depth/shape/location, movements within, lighting factors, and material constituents of object space.

We introduce a three-part categorical scheme for perspective phenomena:

- Environment Factors: refer to the class of perspective phenomena that originate in the physical environment; or the observation context and include ecological processes such as affordance, and invariants (see work of James J. Gibson) and also gestalt perspective processes, etc.

- Extrinsic Factors: refer to the class of perspective phenomena that originate in the optical environment; or overt processes emanating from environmental reality including those traditionally attributable to light ray direction, wavelength (colour), and light ray intensity (detected by eye or classical optical instrument, etc). N.B. Modern methods such as meta-lens technology allow the detection of polarisation and detailed spectral facets that potentially enable simultaneous detection of depth and possibly material information about the spatial object/scene.

- Intrinsic Factors: refer to the class of perspective phenomena that originate in the observation process; or the observation method and processes relayed to the optical device used and a specific optical assembly; indulging factors such as monocular and binocular optical effects, etc.

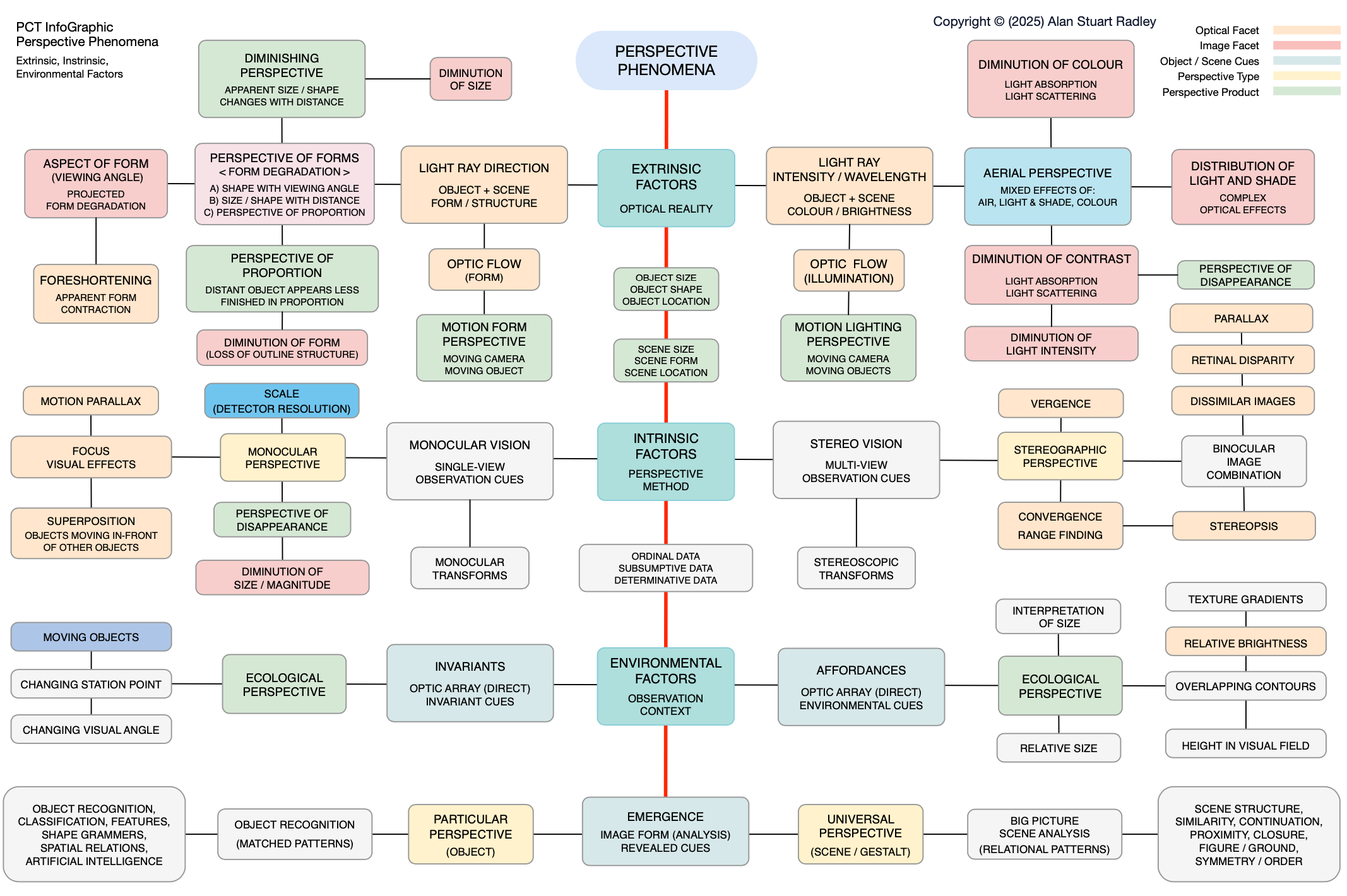

Figure 1 shows a summary of the three classes of perspective phenomena, and depicts a sampling of factors that help to produce the same.

Environmental Factors

Perspective phenomena that originate in the physical environment (or represented physical environment) are known as environmental phenomena, and include all factors that potentially provide information about the true nature of the spatial scene, the objects it contains, and how they may have been (grossly or subtly) transformed in appearance from their true nature in object space.

Particular Object Perspective (fixed image):

- Interpretation of size (relates to Diminution of Size with depth)

- Relative size (size of an object next to an object of known size / depth)

- Object recognition – type, classification, features

- Shape grammars – Degradation of Form (ref. square, circle, etc)

- Shape grammars – Diminution of Form (loss of outline structure)

Particular Object Perspective (changing image):

- Moving objects – depth direction movement (and Diminution of Size)

- Moving objects – lateral direction movement (speed and distance estimation)

Universal Perspective (big picture/scene – see also Emergence theory below):

- Gestalt theory (pattern processing)

- Spatial relations

- Similarity, continuation

- Figure/ground

- Proximity/closure

- Symmetry/order

In addition to the above perspective factors we have the ecological theory; or observation/representation of visual factors that relate to James J.Gibson’s theory of ecological perception. This includes invariants (on movement: some ‘things’ change, others are fixed), affordances (environmental cues), and emergence or pattern recognition analysis within the perspective image/view.

Ecological Perspective (affordances):

- Texture gradients

- Relative brightness gradients

- Affordance of physical actions

- Overlapping contours

- Height in the visual field

Ecological Perspective (invariants):

- Optical array (changes / fixed elements)

- Invariant cues

Gibson’s theory speculates that certain factors are directly (or unconsciously) perceived in a perspective image by humans, including analysis of aspects of the optical array which provide depth, size, location and shape information for objects present in spatial reality. Gibson claims that these factors help the viewer (of spatial reality) to overcome problems such as the correspondence/equivalence problem.

Extrinsic Factors

Perspective phenomena originating in the optical environment (or represented optical environment); extrinsic phenomena refer to overt processes emanating from environmental reality including those attributable to light ray direction, wavelength (colour), and light ray intensity.

According to classic perspective theory, an individual perspective image demonstrates and is recognised by certain visual features (or perspective phenomena). Perspective phenomena refer to the apparent and generalised changes to object/scene visual features that occur according to a particular type of perspective and its inherent processes. Hence, certain forms of graphical perspective can produce the illusion of 3-D space on a flat or 2-D picture surface by employing flat images that evoke specific perspective phenomena—or depth/shape/size/position cues as listed below.

- Diminution of size: remote objects are smaller: size/distance formula.

- Aspect of form: projected shape changes with viewing angle.

- Degradation of form: shape with aspect + distance.

- Diminution of form: remote objects are less distinct.

- Foreshortening (aspect/perspectival): reduced size for receding dimensions.

- Diminution of colour/contrast [intrinsic factor]: Aerial perspective.

- Illumination and shading [intrinsic factor]: light scattering reflection.

- Vanishing points: convergence (at least ONE) set of parallel lines to a vanishing point.

- Vanishing points: central vanishing point for ALL orthogonal lines.

- Vanishing points: single vanishing point for EACH set of parallels in object space (unified image space).

- Convergence of planes to a vanishing trace.

- Lines parallel to picture plane – non-convergence.

- Further parts of the ground plane appear higher up.

- Horizon line formed by infinite extent of ground plane.

- Distortion of metric grid with vanishing points (1,2, or 3).

- ++ other depth/size/shape cues etc.

It is important to note that not all forms of graphical perspective employ/exhibit every single type of perspective phenomenon. Parallel perspective (for example) uses only aspect of form and aspect foreshortening but not diminution of size, perspectival foreshortening, horizon line, or vanishing points.

Intrinsic Factors

Intrinsic phenomena refer to the class of factors originating in the observation process (or represented observation process); or the observation method and processes relayed to the optical device and a specific optical assembly; indulging factors such as monocular and binocular optical effects, etc.

Monocular Vision:

- Moving station point (lateral) – motion parallax/viewpoint triangulation

- Changing station point (lateral) – parallax/viewpoint triangulation

- Moving station point (depth direction) – motion size diminution

- Changing station point (lateral direction) – parallax/viewpoint triangulation

- Focus visual effects / visual acuity

- Superposition – objects moving in front of other objects

- Scale (detector resolution)

Binocular Vision:

- Vergence – changing the convergence angle of each eye’s optical axis

- Convergence range-finding

- Parallax

- Retinal disparity

- Dissimilar images

- Binocular image combination

- Stereopsis

Patently for a real-world situation, all three types of perspective phenomena, environmental, extrinsic and intrinsic factors, must at first be detected by an eye, or other kind of optical instrument. Whereby, the perspective of outlines – or perspective form / geometrical image form is first analysed; prior to analysis of the optical image form or colour/wavelength and brightness/intensity information of detected light rays.

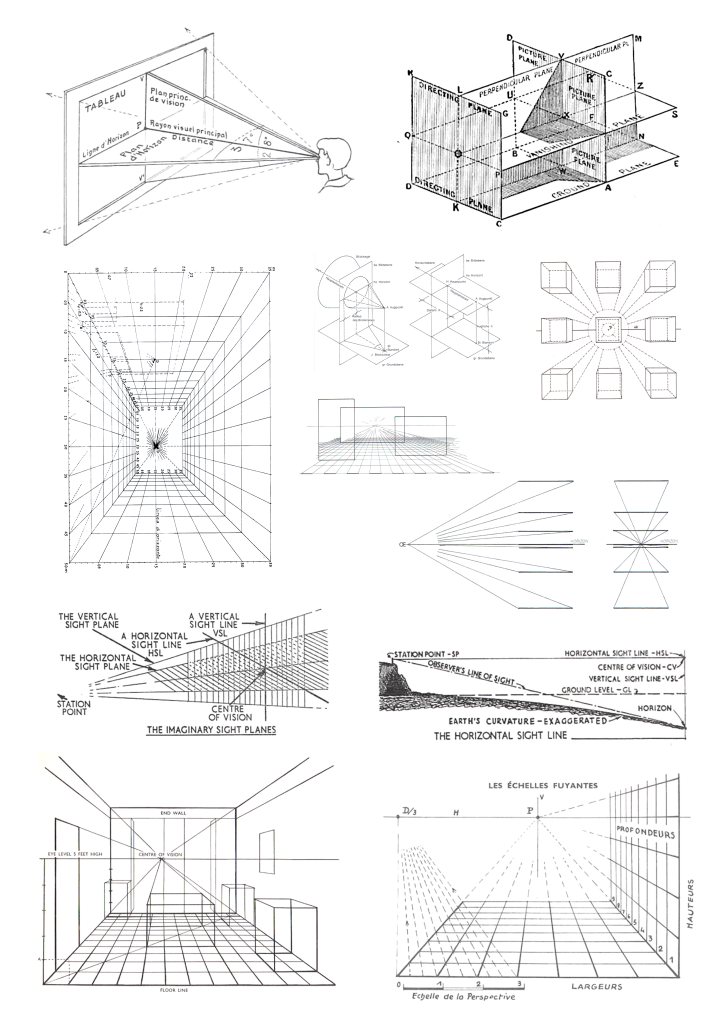

Oftentimes a metric grid or perspective framework structure including sets of parallel lines present in object space, can help us to decode, or make sense of a perspective image of the linear perspective class. It is salient therefore to examine one particular class of perspective: linear perspective in detail as this is one of the most common categories/forms of perspective image.

Axioms of Linear Perspective

Perspective deals with the phenomena of appearance; usually applied to live optical views of spatial reality, photographs of the same; constructed drawings of, or CGI images of, intended spatial objects as seen from some definite point of view.

In appearance, an object may seem very unlike what it is known to be in reality. To understand the differences between physical reality and perspective images/views, principles of perspective have been developed. One example is the fundamental axioms of central/linear perspective as detailed below.

| Axiom 1 | Convergence of Lines to Vanishing Point | Parallel lines appear to converge as they vanish, and to meet at an infinite distance from the observer in an imaginary point called the vanishing point of the system. |

| Axiom 2 | Convergence of Planes to Vanishing Trace | Parallel planes appear to approach one another as they recede from the eye, and to meet at an infinite distance from the observer in an imaginary straight line known as the vanishing trace. |

| Axiom 3 | Line in Plane has its Vanishing Point in Vanishing Trace of Plane | A line lying in a plane must have its vanishing point in the vanishing trace of the plane. This is evident from the manner of locating the vanishing point of a line and vanishing trace of a plane. |

| Axiom 4 | Vanishing Trace of a plane contains VPs of all lines on plane | The vanishing trace of a plane must contain the vanishing points of all lines which lie on the plane. This is the converse of axiom 3. |

| Axiom 5 | Line Intersection of two planes has VP at the intersection of two planes | A line which forms the intersection of two planes, since it lies in both, must have its vanishing point at the intersection of the vanishing trace of the two planes. |

| Axiom 6 | Lines Parallel to Picture Plane – Non-Convergence | Lines in space which are parallel to the picture plane will have their perspectives drawn parallel to one another and not convergent. |

| Axiom 7 | Lines Parallel to Picture Plane – Perspective Parallel to Vanishing Trace | Any line parallel to the picture plane must have its perspective drawn parallel to the vanishing trace of every plane in which it lies. |

| Axiom 8 | Line in which Two Planes Intersect Parallel to Picture Plane | If the line in which two planes intersect is parallel to the picture plane, the vanishing traces of the two planes must be parallel to one another. |

It is perhaps useful at this stage to examine how we humans use the principles and methods of perspective to help us perceive the physical world; before attempting to map these same principles (where appropriate) to artificial types/forms of perspective such as instrument and new media perspective, etc.

Visual Element of System

To begin, we identify the element of a system, another name for a straight line in object space, being one of a particular set or system of parallel lines present in object space. When an observer aligns his axis of vision or line-of-sight directly along a single element, then that line along which the observer sights is called the visual element of the system.

One example is looking directly along a corridor with parallel lines on each corner of the corridor, but looking centrally in mid-air along an imaginary wire that is equally located relative to the corners at each depth point (and directly aligned with the observer’s line-of-sight). This system of parallels all converge toward the infinite extent of said wire at a central vanishing point in the far distance. Ergo, instead of sighting along an actual element, the observer can look in the direction parallel to an element. The direction in which he/she looks may be considered an imaginary element which will lead his eye to the desired vanishing point (of the system of parallel lines in question).

Vanishing Trace and Visual Planes (of System)

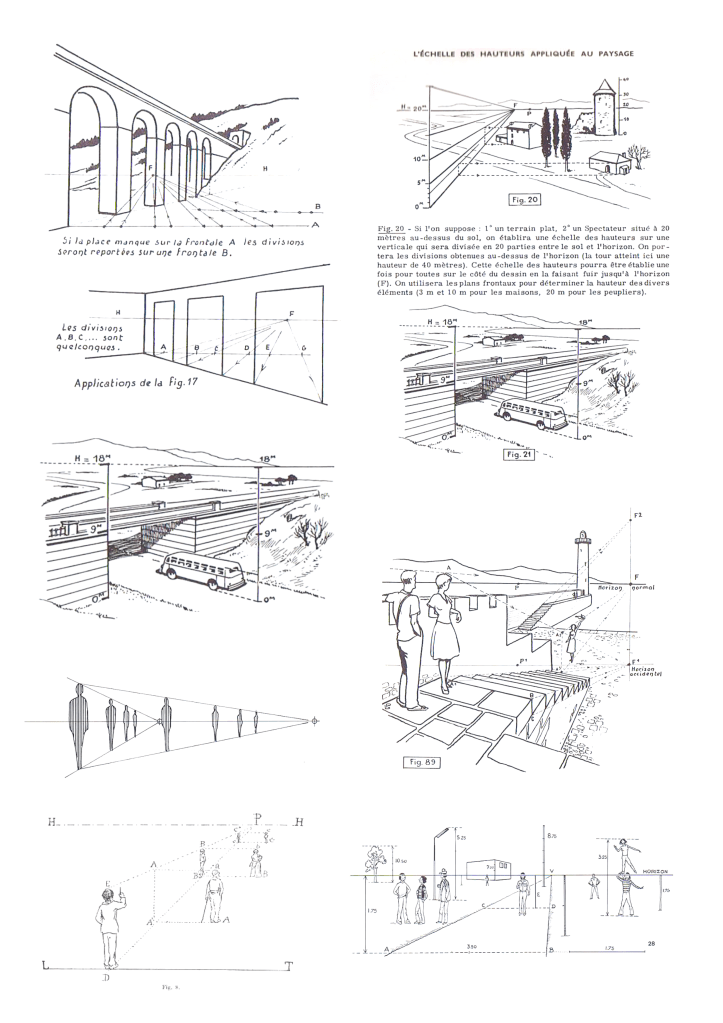

Parallel planes extended an infinite distance appear to meet in a straight line known as the vanishing trace of the planes (see Figure 4: row 3: right). The vanishing trace of the system of horizontal planes will be a horizontal line on a level with the observer’s eye. To this vanishing trace is given the special name of horizon or horizon line.

The horizontal plane along which the observer looks is known as the (horizontal) visual plane of the system (of co-planar planes) – it appears as a horizontal straight line and other horizontal planes of the system seem to approach it (including the ground plane); whereby the horizontal visual plane corresponds to the horizontal eye-line or horizon plane.

The (normal/upright) vertical plane along which the observer looks is known as the (vertical) visual plane of the system (of co-planar planes) – it appears as a vertical straight line (normal to ground plane) and other vertical planes of the system seem to approach it; whereby the vertical visual plane corresponds to the vertical eye-line or vertical plane (at right angles to ground plane).

Sight, Height, Vanishing and Measuring Lines

The above axioms and definitions lead to several automated ways of interpreting perspective images. To begin, a sight line is a line of projection to or through the picture or image plane. A vanishing line is any line on the image, representing one of several parallel lines in object space, that appear to converge together.

A special type of sight-line/vanishing-line is a height-line/measuring-line which is used for making quick vertical measurements in a perspective image. The height line (starting point) occurs at any point where a horizontal line (pointing in any horizontal direction), lying parallel with, but somewhat above the ground plane, meets the picture plane. This (real or imaginary) height line is extended out into (apparent) object space, and represents the top edge of a series of depth point(s). This height line, being horizontal, remains at the same height above the ground plane at all depth locations. You can then plot (or access) the true height of said line at any depth point along a vanishing line because that is a basic rule of perspective, in that this is what a vanishing line is – the apparent height of an object in depth along a vanishing line.

Visual Acuity

Visual acuity is a term derived from Latin (acutus) meaning acute or sharp; and refers to clarity of vision or ability to distinguish detail (especially at a distance).

All optical imaging instruments are limited in terms of the clarity of the visual image/view (of physical reality) that can be captured by that same device. Whereby instrument performance is measured at a specific field-of-view, aperture size, focal length, plus whilst recording related image resolution qualities such as ability to detect detail over specific wavelength ranges and for a particular object distance and depth-of-field, etc. In particular today visual acuity refers to an optical imaging instrument’s depth-of-field in which objects are captured in sharp focus.

A pin-hole camera has an infinite depth-of-field and so in situations with an excellent or high light level, does not need or have the ability to focus with object depth location, whereby the captured image is (ostensibly) sharp at every field-angle and depth-of-field region. However every other optical imager, including the eye, has a region of spatial depth in which objects are captured with excellent acuity or sharp focus, and regions outside of this (often much closer than infinity), are blurred and suffer from a focussing aberration in which object points are spread across several light detection regions or pixels.

Hence, for any optical instrument visual acuity refers to the sharpness of the image(s)/view(s) that are captured by the instrument under a particular set of conditions (ref. image of physical reality).

All of these optical clarity (with depth) effects are known as the perspective of acuity, being a term first discovered and used by Leonardo da Vinci. Ophthalmologists measure visual acuity using a visual acuity chart, such as the Snellen chart seen from a distance of 6m. The chart has lines with letters of increasing size, and the size of the letters on a particular line corresponds to a visual acuity measurement. For example, if you can read the letters on the line labelled “20/20” but not any smaller, then you have 20/20 vision (normal vision).

A camera has a similar relationship between aperture size and reduced depth-of-field. The eye has many other aspects which affect visual acuity, such as binocular vision which further reduces the depth-of-field object space region in which objects are sharply perceived. All optical systems will have limits in visual acuity and spatial resolving power as detailed in the list below.

- Loss of object outline detail due to contrast blurring (atmospheric effects): The apparent object outline length becomes smaller (outline appears less bumpy) as optical depth increases (contrast blurring). This is blurring of object detail with distance, due to atmospheric effects (aerial perspective).

- Loss of outline detail due to reduced projection scale resolution (detector pixel size limitations): The apparent object outline length becomes smaller (outline appears less bumpy) as projection scale is reduced (due to lower projection scale resolution). Hence we have a loss of apparent object outline or detail with reduced projection scale resolution, related to detector pixel size.

- Loss of outline detail due to the perspective of visual acuity (optical focussing limitations with distance): Visual acuity refers to the sharpness of a captured visual image at a distance. It turns out that aspects of perspective phenomena that relate to image sharpness do vary according to the nature of the optical instrument, its operating mode, and in particular the observation scenario facets. Oftentimes only objects located in a narrow region of spacial depth will appear in-focus or be sharply images with good acuity, whereas objects outside of said region will appear out of focus or blurred. Both the human eye and also an optical camera exhibit a similar relationship between increasing the aperture size and a corresponding reduced depth-of-field.

- Limit of outline detail due shape/sufficiency problem (physical limitations or failure of base axioms): A perspective image captures (or represents) physical reality using geometric forms that are valid only at a particular dimensional scale. For example, while making a perspective drawing of a spatial scene using linear perspective, we assume that within the depicted reality (at the chosen scale), the ground-plane, picture/image plane, plus vertical-planes, etc., are all sufficiently flat, and any orthogonal(s) exist as sufficiently parallel and sufficiently rectilinear.

Factors Affecting Image Clarity, Brightness, etc.

Any optical system will have a limit for detector scale resolution beyond which increasing the magnification of the image, or projection size, does not improve or increase the resolving power (ref. size of the smallest discernible detail in object outline). This resolution limit may be due to one or several different factors, including the factors mentioned above [1,2,3,4], and/or wavelength limitations due to the nature of light itself (ref. diffraction limit for instrument aperture), etc.

Oftentimes only objects located in a narrow region of spacial depth will appear in-focus or be sharply imaged with good acuity, whereas objects outside of that region will appear out of focus or blurred. All of these optical effects are sometimes known as the perspective of acuity (or perspective of visual acuity).

Believe it or not, a claim has been made that in the absence of clinical astigmatism, visual acuity is highest for vertical and horizontal lines, and lower for lines at 45 degrees (for example). Plus we know that the retina contains built-in structures for detecting convergence of straight lines or perspective convergence,

Overall it seems that the human visual system is naturally suited to, or has evolved to look for, straight lines in the spatial objects/scenes available to our eyes. Once again this fits in with our earlier discussions on the usefulness of perspective frameworks / metric grids plus the geometrical assumption of upright and right-angled picture plane relative to a flat ground and so to help us humans overcome the equivalence/correspondence problem, plus other problems related to the shape/form sufficiency problem, etc.

To be able to see a spatial reality using perspective mechanism(s), it seems that we humans look for known geometrical structures / frameworks that help us to seek out order and eliminate or ignore excessive visual complexity or disorder in the images/views of reality that we analyse.

Decoding Perspective Phenomena

It is interesting to consider if we fully understand the common ‘twin’ linear perspective phenomena of:

- Horizontal convergence: the apparent convergence of parallel lines towards a vanishing point on the horizon line at the infinite extent of the ground-plane.

- Vertical convergence: the ground-plane appears to climb to meet the horizon line in the far distance.

We can explain these twin linear perspective phenomena as follows…

- Ground-plane visibility: The viewing aspect or plane-of-vision is slightly above the ground-plane: hence the ground-plane is projected at a slight angle (on the picture surface), relative to the horizontal sight line, allowing visibility of the ground-plane surface along its full length; and:

- Apparent convergence of a set of parallel lines (on ground plane), or railway tracks (horizontal convergence): The effects of the perspective phenomenon known as diminution of size (horizontal plane) is understood by consideration of a set of imaginary (or actual) horizontal cross-lines drawn/located between the parallel lines (at standard metric points in depth), the same being equivalent to the track cross-members, whereby said cross-lines gradually decrease in size (horizontal length) until they disappear at a vanishing point (on the horizon line).

- Apparent illusion that the ground-plane is inclined in an upward direction, and gradually climbs to meet the horizon line (vertical convergence): explained by the effects of the perspective phenomenon known as diminution of size (vertical plane): understood by consideration of a set of imaginary vertical lines drawn from the horizontal sight line to the ground plane, many such lines drawn with increasing depth; whereby said lines gradually decrease in size (vertical length) until they disappear at the horizon line; and this gradual cross-line disappearance can be equated to the gradually rising of the ground-plane to meet the sight line (at each point in depth) until it finally disappears at the horizon line. Note also that the ground-plane can never appear to cross, or move above the horizontal sight line, because it is defined as parallel to said sight line (or sight plane) in object space!

Oftentimes a perspective image refers only to the perspective of outlines, and thus to the apparent size/shapes/positions of visible points/lines/planes present in a spatial scene/object. However, by defining perspective in this narrow fashion, we may ignore other (obliquely) related perspective phenomena including colour perspective (aerial perspective), angular distortions, light and shade, and diminution of form or the perspective of proportion/disappearance, etc

Perspective involves consideration of multi-facetted optical phenomena, including foreshortening (aspect, perspectival), scale diminution, convergence of parallels, degradation of form/shape, diminution of form (loss of outline structure), overlapping of elements, height in visual field, etc.

Conclusion

Perspective remains a complex topic because it typically involves the comparison of fundamentally different categories of space. For example, reconciliation of the 3-D space of the physical world (object space), with the 2-D space of graphical or photographic perspective (perspective space). Often, and despite a strong desire to attempt equality/alignment, this reconciliation is difficult (if not impossible) to achieve with perfect correlation; because one deals with dimensions that must map without any physically-based 1:1 correspondence or identical mapping.

Patently information may be lost in this process due to the inherent optical limitations of a single point-of-view, plus aspect-of-form shape changes and scale/shape/size relations, etc., resulting in reduced (or concealed/confused) visual information/details that are to be interpreted in a single visual snapshot (very hopefully). Overcoming aspects of this geometric correspondence—or equivalence—problem is a key ‘goal’ of optical/technical perspective.

Sometimes, the perspective ‘illusion’ becomes so realistic that the viewer forgets that he/she is looking at a mere 2-D representation, and they see ‘into’ the spatial scene as if standing before reality as it appeared to the artist/camera.

Debate continues about the differences between a ‘real’ visual space; and a ‘secondary’ visual space created when looking at a 2-D photograph/movie or painting, etc. In any case, visual perspective remains central to all types of optical perspective; and it is incumbent on us all to learn as much as possible about its wondrous processes and facets/methods.

-- < ACKNOWLEDGMENTS > --

AUTHORS (PAGE / SECTION)

Alan Stuart Radley, April 2020 - 16th May 2025.

---

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Norling, E. 'Perspective Made Easy', 1942.

Radley, A.S. (2023-2025) 'Perspective Category Theory'. Published on the Perspective Research Centre (PRC) website 2020 - 2025.

Radley, A.S. (2025) Perspective Monograph: 'The Art and Science of Optical Perspective', series of book(s) in preparation.

Radley, A.S. (2020-2025) the 'Dictionary of Perspective', book in preparation. The dictionary began as a card index system of perspective related definitions in the 1980s; before being transferred to a dBASE-3 database system on an IBM PC (1990s). Later the dictionary was made available on the web on the SUMS system (2002-2020). The current edition of the dictionary is a complete re-write of earlier editions, and is not sourced from the earlier (and now lost) editions.

---

Copyright © 2020-25 Alan Stuart Radley.

All rights are reserved.

You must be logged in to post a comment.