Perspective is linked with optics, human vision, and inherent geometrical processes. In this section, we explore visual perspective (2nd type).

As defined in perspective category theory; we have two distinct types of visual perspective. Firstly, visual perspective <IMAGING CLASS> (1st type) is when a visual image is used to view, match, represent, and create an illusion of, or an immersion into, the visual appearance of a spatial object/scene. Whereby, this first type of visual perspective covers all categories/forms of optical perspective that deal with visual images, and includes natural and artificial types of perspective.

Secondly, we have visual perspective (2nd type or retinal perspective)—sometimes called ‘true’ perspective—or when a human views a spatial object/scene in physical reality; being a type of natural perspective.

Once again, we are concerned with human vision, or the second type of visual perspective, being a sub-class of the first type of visual perspective, in addition to the optical and technical categories. We begin with a brief introduction to geometrical optics (or light ray optics) and the basic structures/functions of the human visual system.

Generators of the Third Dimension

A key goal of perspective is visualising the world, and in particular obtaining a systematic treatment of depth/scale, whereby perception of distant features of a spatial scene/object is a primary concern.

It is salient to begin our detailed analysis of visual perspective by considering key facts of human visual perception. A vital part of the eye is the detecting surface—the retina—which perceives light-rays emanating (or reflecting) from objects present in spatial reality. However, the retina can only perceive the direction of said rays and not their distances! Put another way, a ‘pixel’ present on the retina stimulated by a light-ray arriving from a particular direction could result from an object point at any position along the same (depth) direction! Object points located at any number of distances from the eye could theoretically result in the same ‘pixel’ stimulation!

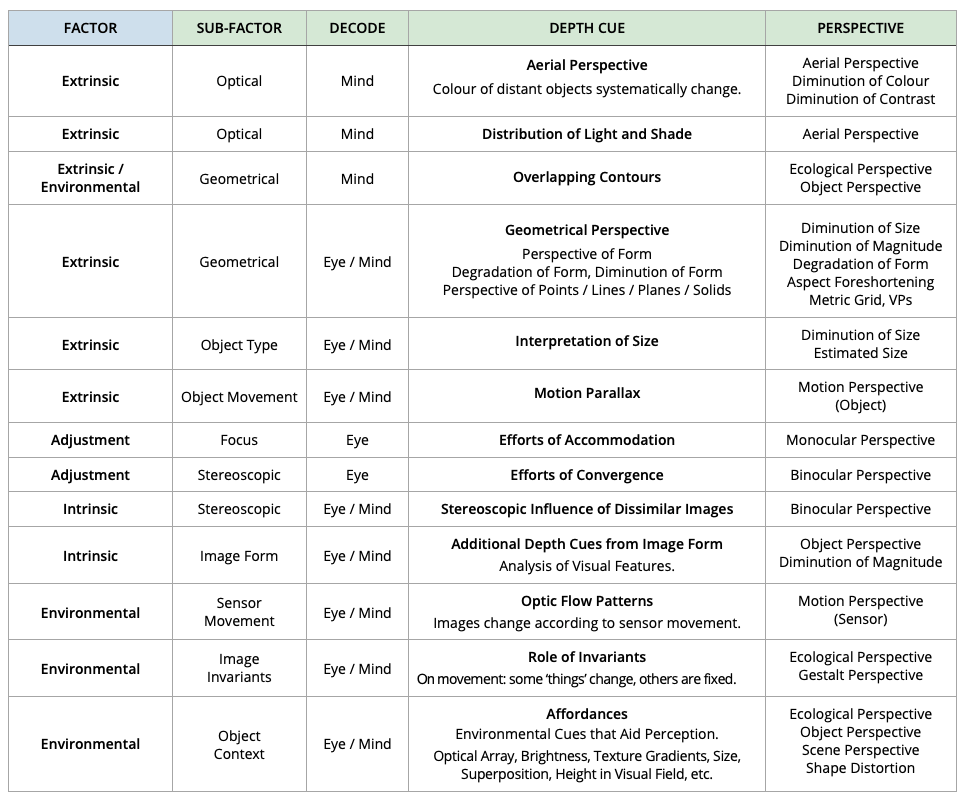

Theoretically and in practice, the eye cannot detect distance in any (direct) way whatsoever! From whence comes the—impression—that we perceive space or depth through the images we receive from our eyes? The answer is that we cannot perceive depth directly, and our visual system employs a range of factors to obtain three-dimensional (3-D) apperceptions. Listed in <TABLE 1> are commonly known ‘generators of the third dimension’, a set of capabilities in the human visual perceptive system termed depth cues.

(horizontal section)

Human Vision and the Depth Cues

People often claim that 3-D as depicted in drawings, paintings, or on a television or computer screen is not “true 3-D”. But they are then unable to explain this statement any further, and sometimes they also add that flat-screen images cannot be true 3-D because they do not show stereoscopic views. Along the way people occasionally mention that stereoscopic glasses are needed for 3-D, one being red and the other blue for the left and right eyes. In one sense, what these people are saying is correct, in that a flat picture does not show stereoscopic images. However, they are incorrect when they assume that only stereoscopic images are “true” 3-D.

Vision experts have long known about the different aspects of depth perception, and that these can be grouped into two categories: monocular cues (cues available from the input of one eye) and binocular or stereoscopic cues (cues available from both eyes). Each of these different “cues” is used by our brains, either independently, or else together, for us to perceive the third dimension.

Not all of the cues are required to be present simultaneously to give us an accurate or realistic impression of 3-D. It has been demonstrated, for example, that we can get a realistic impression of 3-D when just one or two cues are present, as in a linear perspective drawing (aspect and diminution of size, etc), for example.

I think it is worth reminding ourselves of the cues. Monocular cues from one-eyed vision, include perspective of form, motion parallax, colour, distance fog, focus, occlusion, and peripheral vision. Binocular cues from use of two eyes, include stereopsis (binocular disparity, also called binocular parallax) or the difference in shapes and positions of images due to the different vantage points from which the two eyes see the world. Another binocular cue is convergence, and range-finding stereopsis or the human ability to judge the distances to objects due to the angle of convergence between the eyes. Note that some vision experts would argue for the inclusion of other yet more subtle (monocular) optical cues, including occluding edges, surface texture, horizon lines, and other effects due to the ‘direct perception of surface layout’, etc.

The larger number of items on the monocular list, gives a first clue that perhaps stereoscopic vision effects are not the primary way humans perceive depth or the third dimension. You can test this yourself by closing one eye, and immediately you notice that the world still appears to be spread out before you in all its three-dimensional glory! With one eye closed, you may have difficulty with the finer points of depth perception such as picking up a pin off the floor. However, for ordinary (distance-range) tasks, if you lost one eye, you could still rely on the other eye for 3-D vision, in fact by exclusively using the binocular cues.

Those who suggest that stereoscopic 3-D (aka red-blue parallax films) is the only true 3-D, and further that binocular mechanisms are well understood, are claiming that they have more than a head start on some of the greatest experts in human vision who ever lived. World-renowned scientists agree that science has yet to even begin to understand the mechanism(s) by which human beings combine two different (shape-distorted) parallax views into a single correlated image sensation.

Perspective and 3-D

Stereoscopics are not required to give an impression of 3-D. If they were, we would not be able to make much sense of television, films, photographs or even the vast majority of drawings and paintings. These methods, one and all, rely on the monocular cues for depth depiction, yet we have no difficulty understanding the 3-D worlds depicted in which objects lie at different distances from the viewer.

One of the most important monocular cues for depth perception is perspective (or the perspective of form/ lines). Whereby the two most characteristic features are that objects appear smaller in scale as the distance from the observer increases, and also that the scene experiences so-called spatial foreshortening, which is the distortion/ contraction of items when viewed at an angle.

Visual Perspective

The human eye’s primary function(s) are the perception of form, space, and colour. Our visual system evolved to correctly interpret apparent changes to the visual features of a scene/object as viewed from a particular location. The theory, processes, and technical procedures involved in determining how and why these features change is visual optics, or more generally, visual perspective (2nd type).

The mechanisms of perspective rest on the fact that, while we can hear around corners, we cannot see around corners, because light propagates in straight lines. In other words, light is not diffracted at sharp edges, unlike sound (at least to any noticeable degree and under ordinary visual conditions). Also, light typically does lose carried (spatial) information upon (specular) reflection, again unlike sound, which does not lose carried information upon reflection.

Light Rays and Image Formation

Throughout history, the physical basis and processes surrounding light and vision have long been a focus of mystery, awe, wonder and fascination. Scientists and philosophers have expended significant time and effort, and not a little brain power, in attempts to explain all kinds of naturally occurring optical effects.

The concept of light rays arose naturally from a consideration of such phenomena as the shadows cast by illuminated objects, and beams of sunlight; the straight paths of which are made visible by the presence of dust or smoke in the air when they enter a darkened room. According to Isaac Newton (1643 – 1727):

The least Light or part of light, which may be stopped alone without the rest of the Light, or propagated alone, or do or suffer anything alone, which the rest of the light doth not or suffers not, I call a Ray of Light.

Isaac Netwon

According to the light-ray theory, each luminous point (or illuminated object point present in an illuminated three-dimensional scene), sends innumerable light rays into surrounding space. Today we know that matters are a little more complex, and according to wave-particle duality, it is known that light sometimes behaves as if it were comprised of particles (aka photons which travel in straight line paths or as ‘rays’), whereas sometimes light exhibits a wavelike nature and has strange effects that are not always predicted by light-ray theory.

Nevertheless, the light-ray theory remains a good approximation to the behaviour of light in many everyday circumstances, and it is still useful because it provides significant explanation and predictive power. In particular, the light-ray theory does provide a reasonable explanation of how images are formed in the eye and by optical instruments.

For over 500 years scientists have known the basic principles of ray-optics and imaging processes. For example, in the 15th century, Leonardo da Vinci did understand how images can be conveyed by light, and he wrote:

The air is full of an infinity of straight and radiating light rays intersected and interwoven with one another without one occupying the place of another… All bodies together, and each by itself, give off to the surrounding air an infinite number of images which are all in all and each in each part, each conveying the nature, colour, and form of the body which produces it.

Leonardo da Vinci

But patently ray-optics has an even older lineage. Earlier Lucretius (95-51 B.C.) gave a similar account to that of Leonardo, of the centripetal theory of vision as follows:

I maintain therefore, that replicas or insubstantial shapes of things are thrown off from the surface of objects. These we must denote as an outer skin or film, because each particular floating image wears the aspect and form of the object from whose body it has emanated.

Lucretius

Once again, it is true that these rays are a mathematical abstraction of a more complex wave-particle duality of light; nevertheless geometrical optics—or ray optics—remains as useful a concept as ever for explaining how many optical procedures come to be, and in particular nothing more than ray optics is required to explain geometrical or linear perspective (for example).

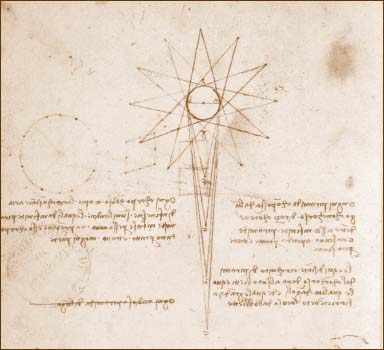

Pyramid of Light: Depicts light rays diverging from a single object point.

discover light dispersion or that white light is comprised of multiple colours;

whilst also demonstrating the rectilinear propagation of light rays (late 1600s).

The Eye

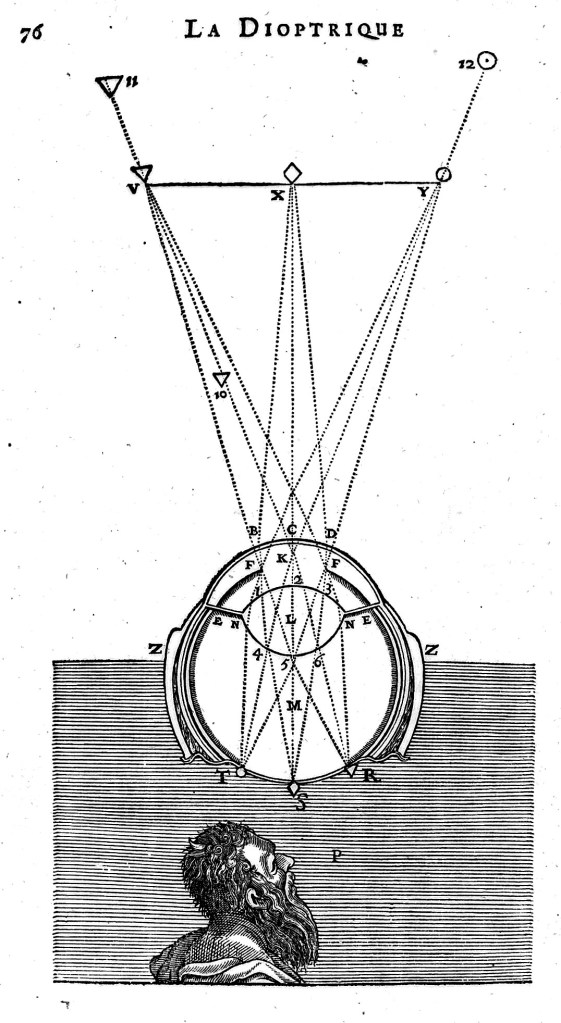

It was Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) who first described (for the public) the modern theory of how the eye works; when in 1604 in his Ad Vitellionem Paralipomena book, he wrote:

Vision, I say, occurs when the image of the whole hemisphere of the external world in front of the eye – in fact a little more than a hemisphere – is projected onto the pink superficial layer of the concave retina.

Johannes Kepler

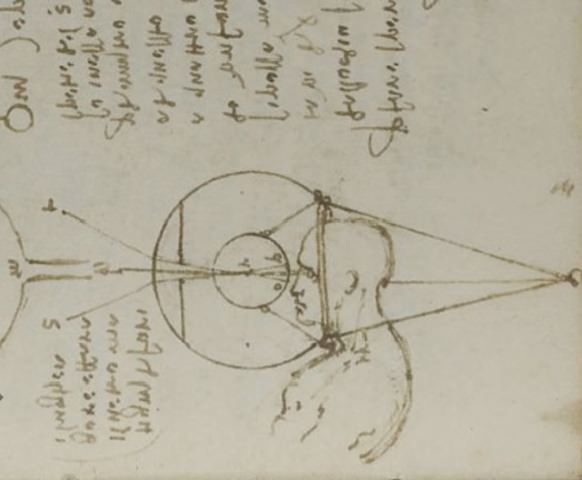

Kepler understood that light from external objects forms an inverted image of these objects on the retina. However, it seems that 100 years earlier, Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519) had a very sophisticated theory of visual optics; and further, he understood clearly that the eye operated like a miniature camera obscura or camera, and projected images onto the retina and after that they were perceived by the brain.

However oddly, Leonardo did not believe that the image (within the eyeball) was inverted; which is strange because he had access to eyes from cadavers and did many eye dissections, detailed anatomical drawings, and even performed optical experiments with eyeballs, etc.

Woodcut by: Rene Descartes, 1637

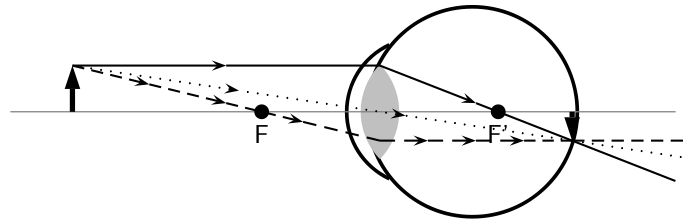

In Figures 1 and 6, we show diagrams of the primary structures of the human eye; accordingly, basic features are explained herein. The marvellous design of the eye begins with shape of the eyeball which approximates a sphere, about 1-inch in diameter. Its outer coat consists of a fibrous white membrane called the sclera. The sclera is replaced (in one bulging circular section) by a transparent window in the front of the eye, called the cornea.

The iris forms a variable aperture that controls the amount of light that passes through the cornea and onto a light-focusing lens that sends light into the eye’s internal structure where it strikes the retina, which covers the greater part of the inside of the eyeball. The retina is covered with numerous receptor cells, the rods, and cones, stimulated by the light pattern that constitutes the retinal image. These light-sensitive cells are connected to the many optic fibres that converge together towards the optic disc, where the optic nerve fibres emerge from the eyeball and go on to the brain.

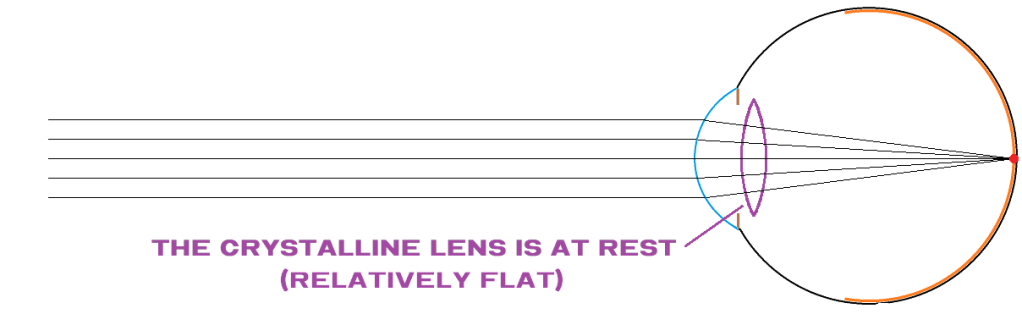

The eye is essentially a camera obscura filled with water. The cornea and lens are responsible for refracting the light entering the eye. This refraction occurs at the cornea, which may be regarded as a convex surface separating air outside from the aqueous humour inside the eye. The lens bends the light further and causes the rays which reach it through the pupil to converge sufficiently to bring them in focus on the retina.

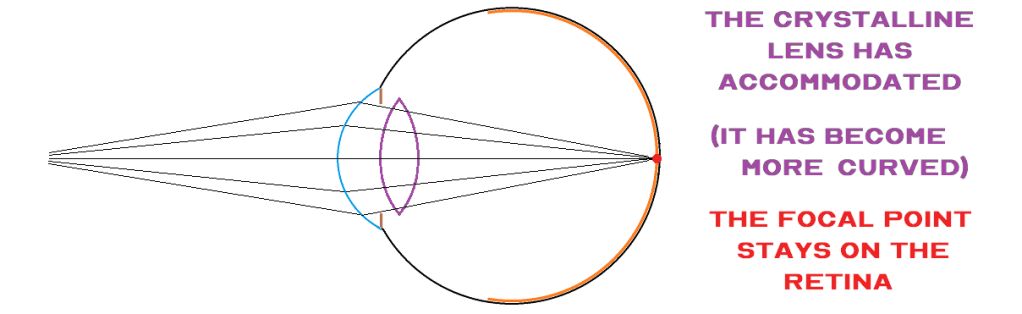

Muscles can pull on the lens to change its shape and hence its converging power, and are responsible for accommodation or sharp differential focussing on objects at varying distances from the eye. Focussing is thus achieved in an entirely different way than in the ordinary photographic camera, which adjusts the length of the camera to focus on objects at different distances.

Visual Perception

What is of primary importance for human vision to operate, is that the optical system of the human eye achieves a ‘point to point’ correspondence between object and its image on the nervous layer that is receptive to light (the retina). The eye must produce distinct or visibly sharp representations—or images—of a three-dimensional scene. The pattern image is largely in-focus without suffering optical blurring effects or optical aberrations and shape distortions etc.

The image produced by the eye is a good approximation of how an object looks from a particular vantage point. Still, the corresponding perceptive processes necessary to achieve sufficient clarity of vision are complex and may involve several trade-offs in image sharpness, field-of-view, and the apparent perception of three-dimensions or depth, etc.

It is essential to realise that many ostensibly pure optical processes happening within the eye, are often complemented (and overridden) by the human perceptual system, as real-time visual processing procedures and psychological processes in the brain. We can summarise human vision by stating that visual perception is extraordinarily complex; and further that whilst much has been learned, certainly even more remains hidden, undiscovered, or unknown to science.

and to increase radii of curvature or optical power and thus to be able to form a sharp imager of close objects.

The Visual Pyramid (of Sight)

Leonardo da Vinci explained perspective by postulating the existence of a ‘point in the eye’ which was the apex of his ‘pyramid of sight’: saying:

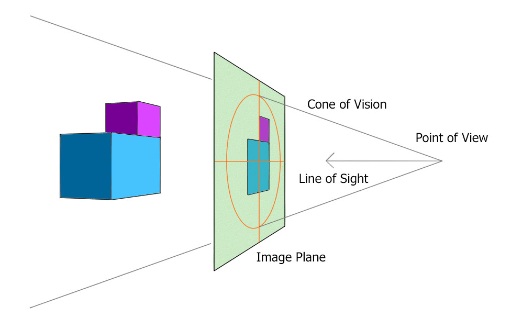

Perspective is nothing else than seeing a place or objects behind a pane of glass, quite transparent, on the surface of which the objects that lie behind the glass are drawn. These can be traced in pyramids to the point of the eye, and these pyramids are intersected by the glass plane… By a pyramid of lines I mean those which start from the surface and edges of bodies; and converging from a distance, meet in a single point. A point is said to be that which [having no dimensions] cannot be divided, and this point placed in the eye receives all the points of the cone.

Leonardo da Vinci

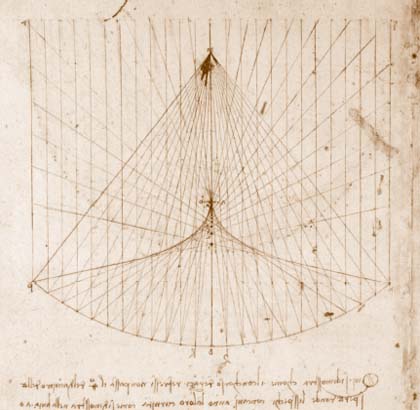

The pyramid-of-sight remains a fundamental concept of visual optics, that explains many features of human vision, not least of which are the various methods and phenomena of visual perspective and related techniques of graphical perspective. The pyramid-of-sight refers to the visual field of each eye in a stationary position. The visual field is the region of outside space in which objects can be seen by this eye when it is in a fixed position, and does not rotate in its orbit. However, if the head is kept immobile but the eye rotates in its orbit, the visual field moves with the eye, and also the point of fixation or centre-of-vision. Consequently, the total field-of-view covered by the moving eye is greater than the visual field itself.

The outer boundary of the pyramid-of-sight is defined by certain rays, the ‘main rays’, ‘chief rays’ or ‘principal rays’, which converge towards a single point in the eye from all of the different object points. Ergo, the beam profile of this pyramid of sight, when used for perspective viewing/drawing, defines the boundary or image outline of objects represented on the picture surface/plane or perspective window. Euclid named such rays the ‘visual rays’. These chief rays define the visual angles subtended by the objects, whose angles are the main subject of visual perspective. Accordingly, the study of visual angles may be called natural perspective.

Note that when dealing with the problem of visual angles and perspective, making an exact determination of the apex of the pyramid of sight is, however, a complex matter because the images of objects at different distances from the eye cannot as a rule be focussed together simultaneously. The apparent position of said point will move about ever so slightly in 3 dimensions (according to object point position) due to focusing and the imaging characteristic of the human eye (aberrations etc).

Visual Acuity – Type A: Field-Of-View

Visual acuity is a term derived from Latin (acutus) meaning acute or sharp; and refers to clarity of vision or ability to distinguish detail (especially at a distance).

The fovea centralis is located in the center of the macula lutea, a small, flat spot located exactly in the center of the posterior portion of the retina. As the fovea is responsible for high-acuity vision it is densely saturated with cone photoreceptors. The macula is about 5.5 mm in diameter, while the fovea is 0.35 mm in diameter. Furthermore, the fovea has about 50 cone cells per 100 micrometers squared and has an elliptical shape horizontally. Given this high cellular concentration, it is expectedly the location of the highest visual acuity, or resolution, in the eye.

The fovea centalis is responsible for sharp central vision (also called foveal vision), which is necessary in humans for activities in which visual detail is of primary importance, such as reading and driving. The fovea centalis covers approximately 18 degrees of the visual field, which is the only region of the eye’s projected field-of-view that gives sharp vision; and to sample a wider field-of-view the eye must constantly scan or move about in its orbit.

We can conclude tht the human eye suffers from loss of outline or visible detail due to the perspective of visual acuity (Type A: limited stationary field-of-view in which images are sharply delineated).

Visual Acuity – Type B: Depth of Field

All optical imaging instruments are limited in terms of the clarity of the visual image/view (of physical reality) that can be captured by that same device. Whereby instrument performance is measured at a specific field-of-view, aperture size, focal length, plus whilst recording related image resolution qualities such as ability to detect detail over specific wavelength ranges and for a particular object distance and depth-of-field, etc. In particular today visual acuity refers to an optical imaging instrument’s depth-of-field in which objects are captured in sharp focus.

A pin-hole camera has an infinite depth-of-field and so in situations with an excellent or high light level, does not need or have the ability to focus with object depth location, whereby the captured image is (ostensibly) sharp at every field-angle and depth-of-field region. However every other optical imager, including the eye, has a region of spatial depth in which objects are captured with excellent acuity or sharp focus, and regions outside of this (often much closer than infinity), are blurred and suffer from a focussing aberration in which object points are spread across several light detection regions or pixels.

A good example is the human eye, whose optical performance does vary in different conditions, such as an ability focus on a close-up region of object space, whereupon, depending on light level and resultant degree of pupil dilation, only objects located in a narrow region of spacial depth will appear in-focus or sharp with good acuity, whereas objects outside of said region appear blurred.

Ergo the human eye suffers from loss of outline or visible detail due to the perspective of visual acuity (Type B: optical focussing type or limitations of optical depth of field with distance).

Visual vs Linear Perspective

Linear perspective (graphical type) refers to the pattern of lines given by the central projection of the objects on a surface, the surface of the picture, the centre of projection being the relevant point in the eye (apex of visual cone with a central position relative to the visual angle or object extent). The perspective projection thus consists of the intersection of the pyramid of sight by the picture surface.

However, natural perspective (all possible types) is more general in scope than linear perspective since each different surface gives a different section of the same pyramid of sight (different picture surface shapes/positions/angles give different perspective views, for example using cone/pyramid/spherical shaped picture planes, etc).

Linear perspective defines the size, shape, and disposition of the objects as drawn in the picture frame or perspective window, with their foreshortening and the apparent overlapping of some near objects upon far objects, for one eye position; but for this position only. Visual perspective itself operates in a different manner with: A) a constantly roaming or changing viewing angle (or sampling of the visual pyramid), and: B) an angle-based distance axiom as opposed to the geometrical based axiom of linear perspective. This latter fact causes visual angles to be quantified differently between the two systems.

In brief, perspective projection is the section of a surface of the pyramid of sight which is seen issuing out of the eye. This projection surface is the spherical surface of the retina, and has certain repercussions in terms of the shape of projected spatial scenes in comparison to linear perspective which projects scenes onto a plane surface. Definitely the visual field of the eye is non-Euclidean in nature, and also curvilinear shaped as experts like Helmholtz proved in the 19th century. Whereas the image space of linear perspective is Euclidean in nature (at least over a relatively narrow field-of-view of around 45-50 degrees). Many people also claim that the shape of the visual field of human vision (image space geometry) is, in fact, spherical, but this argument is by no means proven (certainly it is curved)

In sum, we have described some basic differences between visual and linear perspective; and that most relate to the geometry and shape of the produced image space.

Looking Activities

Renaissance or linear perspective introduced an objective method for recording or copying the physical world at different levels of abstraction in photographs, cinema, engineering drawings, computer images, maps, etc. Accordingly we have three basic methods of optical perspective <IMAGING CLASS>.

First, looking-in/looking-at perspective uses an eye/camera/representation to explore close-up/narrow-field perspective images of a spatial object/area (sphere of revolution perspective). Secondly, looking-out/around perspective uses an eye/camera/representation to explore distant/wide-angle perspective images of a spatial scene (sphere of vision perspective). Finally, looking-through perspective allows seeing ‘through’ spatial scenes and/or perspective windows, or seeing ’inside’ spatial objects; using transparent perspective methods and in combination with special kinds of projection systems/displays (ref. optical/digital methods).

Overall, within culture in general, we see a blending of optical and visual perspective activities/methods/systems with real-time computing, remote-sensing, Internet-Of-Things, Virtual Reality, Artificial Intelligence, etc. Ergo, a new age of super-informative, all-encompassing, real/simulated, and integrated perspective views/images is gathering pace.

Eyes: The Missing User Manual

The most important, yet under-examined category of optical perspective is visual perspective (2nd type or retinal); or the use of the human visual apparatus to comprehend spatial reality and/or interpret images of spatial reality.

Eyesight is central to almost every lived moment, and by implicit association visual perspective is the most practical, ubiquitous, and intimate of processes for sighted humans. However, strangely visual perspective is not taught in schools/universities (in a serious manner). Most people get by with little appreciation of the marvellous capabilities, basic operating principles, or the astonishing results achieved and/or possible with our ‘spatial’ vision.

In this section we are considering uniocular/monocular vision, as detected by one eye, as opposed to binocular vision seen with two eyes; and we are doing so because binocular vision is not the primary way that we humans perceive the third dimension, unless we are talking about an extremely close-range vision task such as picking a needle up off the floor.

Ordinarily, we employ monocular visual cues to perceive depth or 3-D, and perhaps the most important such cue is perspective. Perspective involves consideration of multi-facetted optical phenomena, including foreshortening (aspect, perspectival), scale diminution, convergence of parallels, degradation of form/shape, diminution of form (loss of outline structure), overlapping of elements, height in visual field, etc. Henceforth, it is useful to summarise how we humans can view/decode perspective views/images.

Natural/Single and Composite Perspective(s)

Visual perception involves making a correct interpretation of each perspective view/image, and ultimately by using our eyes as the first (or last) stage in this process. That is, we must adequately frame, capture, prescribe, segment, order, map, index, measure, gauge, and picture/imagine physical space—to accurately comprehend the geometry of each view/image of a spatial scene/object.

Today, we see innumerable perspective views and images created/displayed with a variety of perspective instruments, new media systems, and optical/graphical perspective method(s) on computers, televisions, mobile phones, and in the cinema. As explained often a perspective image/view is the result of several system categories, or is a composite perspective. Plus we look-at, perceive, comprehend, and navigate the world around us using visual perspective.

Correctly interpreting a perspective image (often) entails processing the outcome(s) of one or more perspective method(s)/instrument(s)/system(s). That is, the visual image is analysed consciously or unconsciously; combined with (hopefully, at least some) knowledge of, or in-built notions of, attendant perspective principle(s). Plus often there is a need to make an educated guess as to the geometry of the structural forms being observed.

Decoding Spatial Reality

While looking at the blue-sky without any clouds in sight, we see a formless extent of colour, without any feeling or judgement of depth whatsoever; apart from perhaps the impression of looking into an immensity of open space. No visible geometrical framework/structure means no depth is discernible (space itself is not intrinsically visible).

Contrast that situation with looking down/along a set of parallel railway-tracks, stretching into the distance and apparently converging to a vanishing point. Here we get a real sense of depth, size, angle, and shape for large regions of the depicted space. Such an image is the overt recognition of the railway-track Form, plus standard perspective phenomena including viewing aspect and estimation of diminution of size, which result in converging parallels plus a vanishing-point on the horizon line.

However, physical reality is not comprised solely of railway-track type structures! But rather it contains an infinite variety of different Forms. How then is it possible to correctly ‘decode’ images? First, we apply knowledge of common spatial structures, and how these are sized/shaped plus are visually transformed into perspective image facets (and phenomena) by a category such as linear perspective. Second, we must have knowledge of the other perspective facets: optical assembly (scene + method optics/geometry), plus projection and observation mode(s); and further how these affect perspective phenomena.

Overall, a category such as linear perspective embodies standard mathematical relationship(s) for image transformation factors. But in a real-world situation such as the use of a camera, then apparent distance, size, and shape features may differ significantly from expected results. Such differences increase towards the edges of an eye/lens image, where wide-field perspective distortions can come into play; leading to curvilinear/spherical perspective effects, etc.

Patently for cartographic, astronomical, engineering and technical drawing etc., it is desirable to employ accurate image analysis techniques, which explain use of parallel perspective and/or other counter-distortion perspective types/forms and associated methods. Remember also that elsewhere on this website we have spoken about the importance of perspective framework structures, metric grids, and sets of parallels, all regular forms (in object space) that help the viewer to correctly ‘decode’ a perspective image.

Linear perspective provides a linear structure for the depiction on a surface of the apparent shape, size, and relative position of the objects constituting a spatial scene in 3-D; that is for the representation of linear Forms or what is sometimes called the representation of rectilinear space. This is a form of perspective image/view that most people are familiar with and learned about, or at least learned to recognise and name in school. In fact, this ‘linear’ shaped image, with converging parallels, is so basic to how humans perceive space that a pre-processing physical image detector for converging parallels has been discovered to exist on the retina of the human eye.

Beholder’s Share

Humans see form/structure from a deeply formless world, being one that is beset by a vast amount of disorder or complexity in terms of the geometry of spatial structures. To say nothing of the fact that light rays are fundamentally mixed-up and reflected in all kinds of different directions.

Within this disordered context, visual perspective produces a structured image space that emanates partly from spatial reality, partly from the perspective method/observer, and partly from the visual imager—for example, the human eye and perhaps in combination with a perspective instrument such as a camera. Whereby such a process happens by the application of perspective principles/methods/theory (whether overtly realised or not).

Natural and Artificial Perspective

To analyse visual perspective, firstly, we consider perspective as a process—being of either the natural or artificial class—or as a target object/scene present in a target space (physical or artificial space) that undergoes certain changes before it results in a perspective image, and this we can call the perspective process. In this way we identify two basic kinds of perspective process, firstly natural perspective (including environmental, plus visual or retinal perspective), and secondly artificial perspective (with basic system categories: mathematical, graphical, instrument, simulated, and new media classes).

As we have explained these categories can interrelate on a particular occasion to form composite perspective systems; whereby the category names can also sometimes apply to the outcomes: for example geometric image forms or the perspective of lines/outlines. Also, we explained how blended perspective (merged spaces), combined perspective (overlaid real and represented views), simulated perspective (false or physically adjusted perspective), and mixed perspective (combination of projection and imaging forms) can exist. We have also shown how synthetic perspective or the interaction of natural and artificial types can occur within this scheme.

Two Perspective Pyramid(s)

I think it is worth reiterating a fundamental point in relation to central or linear perspective. Whereby perspective (convergent form) in dealing with distances, employs two opposite ‘perspective’ pyramids:

- The Pyramid of Vision; which has its apex in the eye, and the base as distant as the horizon; whereby each body is full of infinite points, and every point makes a ray… and rays proceeding from the points of the surface of bodies form pyramids (throughout space), and thus each body fills the surrounding air by means of these rays with infinite images, each body becoming the base of innumerable and infinite pyramids… and the point of each pyramid has in itself the whole image of its base… and… the centre-line of the pyramid is full of infinite points of other pyramids, also:

- The Pyramid of Spacial Recession; which has its base towards the eye and the apex at the horizon; whereby objects of equal size, situated in various places, will be seen by different pyramids which will each be smaller in proportion as the object is farther off.

Whereby, the first pyramid includes the visible universe, embracing all objects that lie in front of the eye. And the second pyramid is extended to a spot that is smaller in proportion as it is farther from the eye, and this second pyramid results from the first. Now the interaction of these two pyramids results in a complex system of visual, optical, and physical reference frames which need to be taken into account both to explain and understand/comprehend any perspective image or view.

Types of Space

The ancient Greek experience of space was a tactile one, making a close physical connection between space and Forms in space. We have inserted this tradition in the subject of geometry, whereby the subject of visual/optical/technical perspective despite being ostensibly a visual subject is intimately tied to geometrical concepts.

Our exposition has identified several different kinds of space; including natural/physical space, geometrical space, perspective or image space, instrument space, represented space (analogue and digital kinds), and finally imaginary space. Whereby each kind of space is identified with a corresponding type of spatial reality. We have also binned these into two different kinds of space, being natural and artificial space, which correspond to the two basic kinds of perspective, natural and artificial.

Once again we can also have synthetic perspective, meaning a combination of natural and artificial, but this is a combinational idea that can often be separated out into contributing spacial types. Also we named synthetic, composite, blended, and mixed perspective types which can, and often do, result in the generation of unusual new kinds of space that exhibit special properties.

Despite our wish to clarify and simplify the subject of optical/technical perspective <IMAGING CLASS>, the introduction all of these different types of space/perspective may seem unnecessarily complex. However it is important to realise that perspective is inherently complex, partly due to the variety and composite nature of the imaging systems involved.

One way of simplifying matters, is to remind ourselves that normally we are concerned with the nature and geometry only (or primarily of) the space present in the target or object space. That is, we can consider all of the intermediate perspective categories/methods/principles operating, and hence any intermediate spaces including the final image space which is a representation or model of the target optical space, as being of secondary concern and waypoints on the journey towards understanding/mapping the target space and the Forms contained therein.

But why does this help? Well we can avoid the often arbitrary geometry of intermediate space(s), and focus on decoding target space which normally follows the well-defined principles of Euclidean geometry.

Geometry of Physical Space

A key problem of perspective is identification of the underlying geometry that has produced a perspective image/view. Patently the geometry is dependent upon the involved perspective system(s) or categories, and hence the type/form of perspective being considered.

Patently parallel perspective images are often easier to decode, especially when the object or scene contains straight lines, sets of parallels, right-angled corners, etc, that can all be aligned with a front-elevation, side-elevation, or plan etc. However oftentimes an image is perspectival, or ‘optically warped’, and we humans must then employ knowledge of factors such as depth cues, perspective phenomena, and also common or likely structural forms being observed, and so to overcome the equivalency/correspondence problem.

Normally in local and visual terms, we do assume a type of Euclidean, cartesian reference frame or coordinate system in which we have identified the 6 cardinal directions, north, south, west, east, and up/down. Whereby in a geometrical reference frame, we can identify an object’s visual position, angle, and scale/size, etc. However, we humans use both local and global reference systems, including different types of positional geometry with (for example) latitude and longitude position on the earth’s surface and also astronomical systems such as those explained below.

In astronomy, various coordinate systems are used for identifying the positions of celestial objects (satellites, planets, stars, galaxies, etc.) relative to a fixed reference frame. Coordinate systems in astronomy can specify an object’s relative position in three-dimensional space, but also plot its apparent direction on a celestial sphere, especially if the object’s distance is vast, or unknown. The primary celestial sphere is a fixed imaginary sphere that surrounds Earth and is used to calculate the positions of objects in the night sky (at a specific time).

Spherical coordinates, projected onto a celestial sphere, are similar to the geographic coordinate system used on the Earth’s surface. Also, changing horizontal coordinates use a celestial sphere centered on the observer. Azimuth is measured eastward from the north point (sometimes from the south point) of the horizon; altitude is the angle above the horizon. Whereby each coordinate system is named after its choice of fundamental origin/projection-plane. Astronomical systems include alt-az, equatorial, ecliptic, galactic and super-galactic.

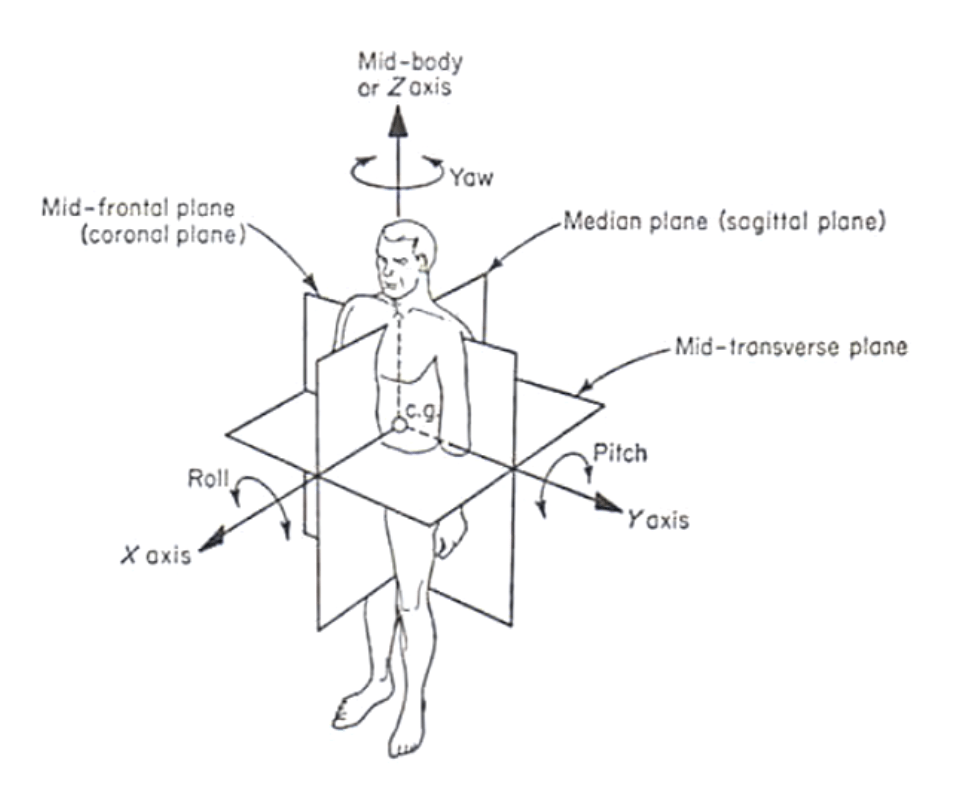

Human Spatial Orientation

Considering a perspective image/view captured by visual or retinal perspective, optical or instrument perspective; then we have the basic problem of establishing a stable or moving head/eye position in relation to stable external reference frame. Whereby we can identify the positions/angles of objects in the external world surrounding us (depth determinations we shall ignore at present). But what is the nature of this reference frame, and what are its components?

According to the basic definition, two lines or axes are required to specify an orientation. One axis we refer to as the fixed or standard axis, and the other is the variable axis. Both types of axis may external to the body, or both may be internal, or one may be external and the other internal.

Orientation behaviours:

- Judging Angles

- Judging Direction (e.g. inclination, compass direction)

- Setting a point to eye level (horizontal, vertical)

- Gravitational orientation of the body (up / down)

- Geographical orientation of the body (N/W/S/E)

- Ego-centric – setting a line parallel with the body axis

- Ego-centric – setting a point to the median plane

- Relative orientation of body parts

The top 3 of judgements (1-3) may be made without knowledge of the orientation of any body-axis. The other main group of orientation tasks (4 -7) involves judging the angle between between a body-axis and either a gravitational axis or a geographical-axis, and judging the angle between a body-axis and the external line or axis anchored at one end of the body. Accordingly, we can establish a convenient body-coordinate system of ego-centric axes of rotation, which establishes the principal planes and axes of the human body as shown below.

Remember in this section we are considering perspective views/images that are related to visual or retinal perspective; whereby the image is either a real-time view of physical reality, a camera view of the same, or else a purported representation (drawing, painting, photograph, etc) of a view of spatial reality. In any case this is how we humans naturally make sense of the world in visual terms, and using an ego-centric coordinate system, we use this to make a ‘picture’ of any spatial reality and associated spatial Forms.

Translating between the visual reference frame and other more general physical or world-oriented frames is a natural perspective process and one that we shall look at in the next sections.

Visual Direction

In terms of the direction of vision, the human visual system has three main tasks:

- Provide information to enable an observer to know where a seen object is in relation to the body, and to know how this is involved in real-world events, plus to determine movement.

- To maintain the accurate functioning of the above mechanism in spite of changes to the position of the eyes, head, body (and/or moving vehicle or view containing the same).

- Provide a metric for the visual system to provide a metric of judging directions and distances that are consistent over the whole field of view.

All three of these aspects of human vision are made in relation to the initial detection surface of the image-capturing or detection instrument (the eye when looking at reality directly without optical aids). Notably, however, one or any of the intermediate instruments/systems involved can change how a direction appears, or is mathematically collocated as an angle or distance value in object or image space.

We can call the instrument that initially captures the image from a target reality the primary perspective instrument, and all others up to but not (usually) including the human eye on the back of said systems, the perspective intermediate instruments. The final image viewed by the eye is the visual or retinal image.

Patently when it comes to visual perspective, we have a series of registration problems, whereby we transpose size, positions, and angles, from object space to one or more image spaces contained in a set of intermediate and final or primary image spaces. We do not have space to examine the problems or any solutions here. Remember also the scale / shape / size, and shape/sufficiency problem(s) which come into play in many such problem areas.

However, a key problem of human vision is how to reconcile the separately angled vision of two eyes with a single viewpoint. Each eye sees a different degree of distortion, in terms of angles and positional information, and hence the question arises as to how the visual system or mind is able to create one visual direction from two! Several solutions have been proposed, but perhaps the best is Hering’s law of identical binocular directions (see next section). How the human visual systems solves such a problem might seem like an arcane and unnecessary detail of ophthalmology; but the fact that this key problem can be solved, and the details of how, are central topics in natural/visual perspective and also by extension artificial and synthetic perspective theory.

Ergo, human vision is a strange amalgamation of physical/physiological/psychological optics.

Object Position

In 1942, Hering identified what he called ‘visual lines’: ‘a visual line is the locus of all points fixed relative to the eye which stimulates a given point on the retina’.

This defines a basic oculocentric direction, based on an imaginary Cyclopion eye located in the middle of right and left eyes, a direction which is also known as the ‘visual axis’. Whereby for any position of the eyes, all points on a particular visual line are normally judged to be in alignment, that is, to be geometrically superimposed even if at different distances. This is the law of oculocentric visual direction.

In any case, after much theoretical work, scientists determined that ‘all visual lines of both eyes are judged to point to one and the same projection centre, after the visual system has processed data from both eyes. This projection centre is assumed to lie at the centre of the axis joining the centres of the two eyes, that is the interocular axis, and is referred to as the cyclopian eye.

The related law of identical visual directions, states that every retinal point in the binocular field has a partner in the retina of the other eye with identical directional value (at least potentially and under certain commonly produced conditions). Whereby, we note that this real-time visual processing procedure is similar to the registration processes which must take place when passing an image through the optical image chain—and across multiple perspective categories/spaces; whereby a mathematical process of transposition occurs and for accuracy/precision these spaces must be aligned or posses regular geometrical relations (at least for object and final image spaces), enabling perspective measurements to be taken from the final image by use of an appropriately mapped image plate-scale or magnification, field-of-view, and resolution factors etc.

An important feature of human vision is that unmoving visual objects always appear in the same direction, when observed from a stationary point of view and with a fixed position eyeball and head. To be aware of their direction, of there ‘whereness’ in general, is a feature of the fact that light travels in straight lines. Ergo, light direction as it impinges upon the eye, is the most important and usually a sufficient depth cue for the object’s direction. But this is not always the case, since castles appear upside down when viewed in lakes, and mirrors show virtual objects that are not really where they appear to be! We must conclude that the object of attention is not always in the direction indicated by the light entering the eye.

One final point must be made, that the visual space of retinal vision is complex and varies according to the details of specific scenarios, and so contains many factors that are dependent upon object distances, imaging systems used, visual-field, focussing, binocular convergence and many other factors.

Shape Grammars

James J. Gibson pointed out that for a real-time view of physical space, and a generated/recorded image to provide the same information about object space; the delimited surface must process light in such a way that it reflects a particular sheaf of rays to a given point which is similar to the same sheaf of rays from the original object/scene to that point. Ergo, Gibson said that a picture, whilst being ostensibly a two-dimensional picture, its surface is nevertheless also a peculiar sheaf of rays generated that are in some sense equivalent to the original sheaf coming from the 3-D scene.

Consider the generation of a perspective view as follows: a natural or environmental optical view is captured with a camera, then processed within a new media system, before being presented on a television monitor and then looked at using visual perspective by a human. In the latter example, the optical image ‘chain’ includes both natural and artificial processes, which can, may, or will alter the perspective forms present in the final image. And these changes can be significant, including: spatial projection/construction, graphical calculation/modelling, mathematical calculation/modelling, plus optical and computer modelling, etc.

We can conclude that the best way of understanding the origins of, and processes that formed, a perspective image/view; is to acknowledge that the vast majority of these are both structurally and procedurally composite and have complex origins. The only at least partial exception are natural perspective processes including environmental optics such as shadow casting, or astronomical seasons, etc; which may be in some sense automatically perceived using natural or built-in image processing (inheretited from our ancestors).

But if complexity was the dominant factor in human vision, then we humans would not be able to make much sense of spatial images. Rather when looking at a perspective image, human vision seeks to identify various common geometrical/optical transformation processes of common shapes such as regular flat shapes, regular polygons, straight and regularly curved lines, converging lines and vanishing points, and a horizon line. Whereby, we attempt to simplify the image structure(s), and associated perceptual tasks. Finally metric grids and other framework structure are common ways to rapidly and accurately encode/decode an image of spatial reality.

Overall, we can conclude that accurate perception, comprehension, and understanding of a perspective image/view is only possible when we can make a series of decoding procedures, simplifications, assumptions or projections of order onto image structures, plus make well-founded guesses, about the nature of the forms under consideration; including:

- Target Spacial Reality (nature of)

- Original Forms – Lines / Planes / Solids (Polygons etc)

- Original Framework Structures (metric grid etc)

- Visual Frameworks: Sight & Height lines, Visual Element.

- Imager: Assembly, Projection, and Observation Modes

- Image Chain (Categories + Phenomena)

- Decoding Image of Spatial Reality

We can usefully name all of these and other related attendant procedures; as the rapid, and efficient perception, recognition, and combination/aggregation of image shapes/Forms; or the application of shape grammars to the perspective reversal/inverse process, or the spatial object/scene recognition/decoding problem from the given perspective image/view.

Patently, in terms of a perspective image/view, we have two basic types of shape grammars. Firstly, we have scene-based shape grammars such as the appearance of the distorted metric grid of linear perspective, a visible horizon line, converging sets of parallel lines, etc. Familiarity with, and accurate perception and decoding of such scene-based shape grammars can provide accurate readings of large-scale structural frameworks, or contextual location/size/direction/distance information within a perspective image/view. Next, we have object-based shape grammars whose familiarity allows localised object shape/size/position/angle readings and associated object type/form recognition judgments.

Overall, familiarity with shape grammars can play a significant role in teaching us how to correctly interpret perspective images/views, both individually, and collectively, and also for AI and computer vision systems.

-- < ACKNOWLEDGMENTS > --

AUTHORS (PAGE / SECTION)

Alan Stuart Radley, 21st January 2023 - 16th May 2025.

---

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Radley, A.S. (2023-2025) 'Perspective Category Theory'. Published on the Perspective Research Centre (PRC) website 2020 - 2025.

Radley, A.S. (2023-2025) 'Dimensions of Perspective', book in preparation.

Radley, A.S. (2023-2025) 'The Dictionary of Perspective', book in preparation. The dictionary began as a card index system in the 1980s; before being transferred to a dBASE-3 database system on an IBM PC (1990s). Later the dictionary was made available on the web on the SUMS system (2020-2025).

---

Copyright © 2020-25 Alan Stuart Radley.

All rights are reserved.

You must be logged in to post a comment.